A grisly trade in human body parts leaves relatives grieving

and some recipients at risk of life-threatening disease.

By Kate Willson, Vlad Lavrov,

Martina Keller, Thomas Maier and Gerard Ryle

July

17, 2012

.

.

On February 24, Ukrainian authorities made an alarming

discovery: bones and other human tissues crammed into coolers in a grimy white

minibus.

From day one, everything was forged; everything, because we could. As long as the paperwork looked good, it was fine

Investigators grew even more intrigued when they found, amid

the body parts, envelopes stuffed with cash and autopsy results written in

English.

.

Bottles of human tissue labelled ''Made in Germany,

Tutogen" that were were seized by Ukrainian authorities.

MykolaivSeizure1.jpg

What the security service had disrupted was not the work of

a serial killer but part of an international pipeline of ingredients for

medical and dental products that are routinely implanted into people around the

world.

The seized documents suggested that the remains of dead

Ukrainians were destined for a factory in Germany belonging to the subsidiary

of a US medical products company, Florida-based RTI Biologics.

RTI is one of a growing industry of companies that make

profits by turning mortal remains into everything from dental implants to

bladder slings to wrinkle cures.

The industry has flourished even as its practices have roused concerns about how tissues are obtained and how well grieving families and transplant patients are informed about the realities and risks of the business.

The industry has flourished even as its practices have roused concerns about how tissues are obtained and how well grieving families and transplant patients are informed about the realities and risks of the business.

.

''I was in shock'' ... Kateryna Rahulina says she did not give

permission for the body of her mother Olha to be harvested. Photo:

Konstantin Chernichkin/Kyiv Post

In the US alone, the biggest market and the biggest

supplier, an estimated two million products derived from human tissue are sold

each year, a figure that has doubled over the past decade.

It is an industry that promotes treatments and products that

literally allow the blind to see (through cornea transplants) and the lame to

walk (by recycling tendons and ligaments for use in knee repairs).

It's also an industry fueled by powerful appetites for bottom-line profits and fresh human bodies.

It's also an industry fueled by powerful appetites for bottom-line profits and fresh human bodies.

In the Ukraine, for example, the security service believes

that bodies passing through a morgue in the Nikolaev district, the gritty

shipbuilding region located near the Black Sea, may have been feeding the

trade, leaving behind what investigators described as potentially dozens of

“human sock puppets” ~ corpses stripped of their reusable parts.

Industry officials argue that such alleged abuses are rare,

and that the industry operates safely and responsibly.

For its part, RTI didn't respond to repeated requests for

comment or to a detailed list of questions provided a month before this

publication.

In public statements the company says it “honours the gift

of tissue donation by treating the tissue with respect, by finding new ways to

use the tissue to help patients and by helping as many patients as possible

from each donation".

'OUR MISFORTUNE'

Despite its growth, the tissue trade has largely escaped

public scrutiny. This is thanks in part to less-than-aggressive official

oversight ~ and to popular appeal for the idea of allowing the dead to help the

living survive and thrive.

An eight-month, 11-country investigation by the

International Consortium of Investigative Journalists has found, however, that

the tissue industry's good intentions sometimes are in conflict with the rush

to make money from the dead.

Inadequate safeguards are in place to ensure all tissue used

by the industry is obtained legally and ethically, ICIJ discovered from

hundreds of interviews and thousands of pages of public documents obtained

through records requests in six countries.

.

.

GRAPHIC VIDEO: THE TRADE IN BODY PARTS

Despite concerns by doctors that the lightly regulated trade

could allow diseased tissues to infect transplant recipients with hepatitis,

HIV and other pathogens, authorities have done little to deal with the risks.

In contrast to tightly monitored systems for tracking intact

organs such as hearts and lungs, authorities in the US and many other countries

have no way to accurately trace where recycled skin and other tissues come from

and where they go.

At the same time, critics say, the tissue-donation system

can deepen the pain of grieving families, keeping them in the dark or

misleading them about what will happen to the bodies of their loved ones.

Those left behind, like the parents of 19-year-old Ukrainian

Sergei Malish, who committed suicide in 2008, are left to cope with a grim

reality.

At Sergei's funeral, his parents discovered deep cuts on his

wrists. Yet they knew he had hanged himself.

They later learned that his body parts had been recycled and

shipped off as “anatomical material".

“They make money with our misfortune,” Sergei's father said.

AN AWKWARD SILENCE

During the transformational journey tissue undergoes ~ from

dead human to medical device ~ some patients don't even know that they are the

final destination.

Doctors don't always tell them that the products used in

their breast reconstructions, penis implants and other procedures were

reclaimed from the recently departed.

Nor are authorities always aware of where tissues come from

or where they go.

The lack of proper tracking means that by the time problems

are discovered some of the manufactured goods can't be found. When the US

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention assists in the recall of products

made from potentially tainted tissues, transplant doctors frequently aren't

much help.

“Oftentimes there's an awkward silence. They say, 'We don't

know where it went,'” said Dr Matthew Kuehnert, the CDC's director of blood and

biologics.

“We have bar codes for our [breakfast] cereals, but we don't have bar codes for our human tissues," Kuehnert said. "Every patient who has tissue implanted should know. It's so obvious. It should be a basic patient right. It is not. That's ridiculous.”

Since 2002 the US Food and Drug Administration has

documented at least 1352 infections in the US that followed human tissue

transplants, according to an ICIJ analysis of FDA data. These infections were

linked to the deaths of 40 people, the data shows.

One of the weaknesses of the tissue-monitoring system is the

secrecy and complexity that comes with the cross-border exchange of body parts.

The Slovaks export cadaver parts to the Germans; the Germans

export finished products to South Korea and the US; the South Koreans to

Mexico; the US to more than 30 countries.

Distributors of manufactured products can be found in the

European Union, China, Canada, Thailand, India, South Africa, Brazil, Australia

and New Zealand. Some are subsidiaries of multinational medical corporations.

The international nature of the industry, critics claim, makes

it easy to move products from place to place without much scrutiny.

“If I buy something from Rwanda, then put a Belgian label on

it, I can import it into the US. When you enter into the official system,

everyone is so trusting,” said Dr Martin Zizi, professor of neurophysiology at

the Free University of Brussels.

Once a product is in the European Union, it can be shipped

to the US with few questions asked.

“They assume you've done the quality check," Zizi said. "We are more careful with fruit and vegetables than with body parts.”

PIECE OF THE ACTION

Inside the marketplace for human tissue, the opportunities

for profits are immense. A single, disease-free body can spin off cash flows of

$US80,000 to $US200,000 for the various non-profit and for-profit players

involved in recovering tissues and using them to manufacture medical and dental

products, according to documents and experts in the field.

.

.

It's illegal in the US, as in most other countries, to buy or sell human tissue. However, it's permissible to pay service fees that ostensibly cover the costs of finding, storing and processing human tissues.

Almost everyone gets a piece of the action.

Ground-level body wranglers in the US can get as much as

$US 10,000 for each corpse they secure through their contacts at hospitals,

mortuaries and morgues. Funeral homes can act as middlemen to identify

potential donors. Public hospitals can get paid for the use of tissue-recovery

rooms.

And medical products multinationals like RTI? They do well,

too. Last year RTI earned $US 11.6 million in pretax profits on revenues of

$US 169 million.

Phillip Guyett, who ran a tissue recovery business in

several US states before he was convicted of falsifying death records, said

executives with companies that bought tissues from him treated him to $US 400

meals and swanky hotel stays. They promised: “We can make you a rich man.”

It got to the point, he said, that he began looking at the dead “with dollar signs attached to their parts". Guyett never worked directly for RTI.

It got to the point, he said, that he began looking at the dead “with dollar signs attached to their parts". Guyett never worked directly for RTI.

SMOKED SALMON

Human skin takes on the colour of smoked salmon when it is

professionally removed in rectangular shapes from a cadaver. A good yield is

about 5500 square centimetres.

After being mashed up to remove moisture, some is destined

to protect burn victims from life-threatening bacterial infections or, once

further refined, for breast reconstructions after cancer.

The use of human tissue “has really revolutionized what we

can do in breast reconstruction surgery”, explains Dr Ron Israeli, a New York

plastic surgeon.

“Since we started using it in about 2005, it's really become

a standard technique.”

A significant number of recovered tissues are transformed

into products whose shelf names give little clue to their actual origin.

They are used in the dental and beauty industries, for

everything from plumping up lips to smoothing out wrinkles.

Cadaver bone ~ harvested from the dead and replaced with PVC

piping for burial ~ is sculpted like pieces of hardwood into screws and anchors

for dozens of orthopaedic and dental applications.

Or the bone is ground down and mixed with chemicals to form

strong surgical glues that are advertised as being better than the artificial

variety.

“At the basic level what we are doing to the body, it's a

very physical ~ and I imagine some would say a very grotesque ~ thing,” said

Chris Truitt, a former RTI employee in Wisconsin.

“We are pulling out arm bones. We are pulling out leg bones.

We are cutting the chest open to pull the heart out to get at the valves. We

are pulling veins out from the inside of skin.”

Whole tendons, scrubbed cleaned and rendered safe for

transplant, are used to return injured athletes to the field of play.

There's also a brisk trade in corneas, both within countries

and internationally.

Because of the ban on selling the tissue itself, the US

companies that first commercialized the trade adopted the same methods as the

blood collection business.

The for-profit companies set up non-profit offshoots to

collect the tissue ~ in much the same way the Red Cross collects blood that is

later turned into products by commercial entities.

Nobody charges for the tissue itself, which under normal

circumstances is freely donated by the dead (via donor registries) or by their

families.

Rather, tissue banks and other organizations involved in the

process receive ill-defined “reasonable payments” to compensate them for

obtaining and handling the tissue.

“The common lingo is to talk about procurement from donors

as 'harvesting', and the subsequent transfers via the bone bank as 'buying' and

'selling,' ” wrote Klaus Hoyer, from the University of Copenhagen's Department

of Public Health, who talked to industry officials, donors and recipients for

an article published in the journal BioSocieties.

“These expressions were used freely in interviews. However,

I did not hear this terminology used in front of patients.”

A US-government funded study of the families of US tissue

donors, published in 2010, indicates many may not understand the role that for-profit

companies play in the tissue donation system.

Seventy-three per cent of families who took part in the

study said it was “not acceptable for donated tissue to be bought and sold, for

any purpose".

FEW PROTECTIONS

There is an inherent risk in transplanting human tissues.

Among other things, it has led to life-threatening bacterial infections, and

the spread of HIV, hepatitis C and rabies in tissue recipients, according to

the CDC.

Modern blood and organ collection is bar-coded and strongly

regulated ~ reforms prompted by high-profile disasters that had been caused by

the poor screening of donors. Products made from skin and other tissues,

however, have few specific laws of their own.

In the US, the agency that regulates the industry is the

Food and Drug Administration, the same agency that's charged with protecting

the nation's food supply, medicines and cosmetics.

The FDA, which declined repeated requests for on-record

interviews, has no authority over health care facilities that implant the

material. And the agency doesn't specifically track infections.

It does keep track of registered tissue banks, and sometimes

conducts an inspection. It also has the power to shut them down.

The FDA largely relies on standards that are set by an

industry body, the American Association of Tissue Banks. The association

refused repeated requests over four months for on-record interviews.

It told ICIJ during a background interview last week that

the "vast majority" of banks recovering traditional tissues such as

skin and bone are accredited by the AATB. Yet an analysis of AATB-accredited

banks and FDA registration data shows about one third of tissue banks that

recover traditional tissues such as skin and bone are accredited by the AATB.

The association says the chance of contamination in patients

is low. Most products, the AATB says, undergo radiation and sterilization,

rendering them safer than, say, organs that are transplanted into another

human.

"Tissue is safe. It's incredibly safe," an AATB

executive said.

There is little data, though, to back up the industry's

claims.

Unlike with other biologics regulated by the FDA, agency

officials explain, firms that make medical products out of human tissues are

required to report only the most serious adverse events they discover. That

means that if problems do arise, there's no guarantee that authorities are

told.

And because doctors aren't required to tell patients they're getting tissue from a cadaver, many patients may not associate any later infection with the transplant.

On this point, the industry says it is able to track the

products from the donors to the doctors, using their own coding systems, and

that many hospitals have systems in place to track the tissues after they're

implanted.

.

.

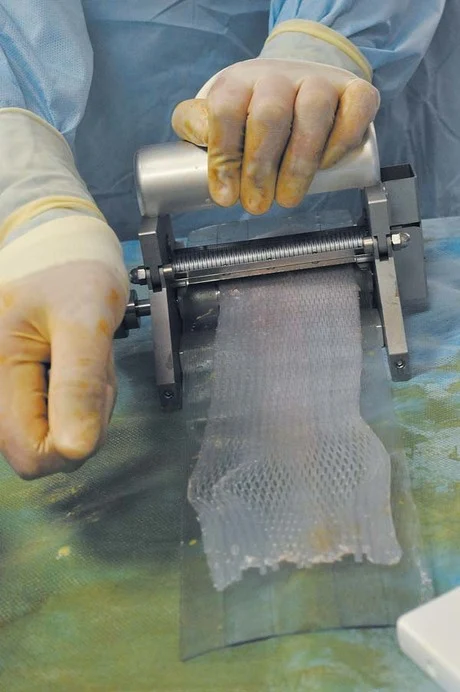

After it is processed, human skin looks similar to thin layers

of smoked salmon. Here, it is being meshed before application on a burns patient

at Queen Astrid Military Hospital in Brussels, Belgium. (Mar Cabra/ICIJ)

But no centralized regional or global system assures products can be followed from donor to patient.

“Probably very few people get infected, but we really don't

know because we don't have surveillance and we don't have a system for

detecting adverse events,” the CDC's Kuehnert said.

The FDA recalled more than 60,000 tissue-derived products

between 1994 and mid-2007.

The most famous recall came in 2005. It involved a company

called Biomedical Tissue Services, which was run by a former dental surgeon,

Michael Mastromarino.

Mastromarino got many of his raw materials from undertakers

in New York and Pennsylvania. He paid them up to $US1000 per body, court

records show.

His company stripped bodies of their bones, skin and other

usable parts, then returned them to their families. The families, ignorant of

what happened, buried or cremated the evidence.

One of more than 1000 bodies that were dismembered was that of the famous BBC broadcaster Alistair Cooke.

Products made from the stolen human remains were shipped to

Canada, Turkey, South Korea, Switzerland and Australia. More than 800 of those

products have never been located.

It later came out in court that some of the tissue donors

had died from cancer and that none had been tested for pathogens like HIV and

hepatitis.

Mastromarino falsified donor forms, lying about causes of

death and other details. He sold skin and other tissues to several US

tissue-processing firms, including RTI.

“From day one, everything was forged; everything, because we

could. As long as the paperwork looked good, it was fine,” said Mastromarino,

who is serving a 25-to-58-year prison sentence for conspiracy, theft and abuse

of a corpse.

GLOBAL SHERIFF

Each country has its own set of regulations for the use of

products made from human tissue, often based on laws that were originally

intended to deal with blood or organs.

In practice, though, because the US supplies an estimated

two-thirds of the world's human-tissue-product needs, the FDA has effectively

been left to act as sheriff for much of the planet.

Foreign tissue establishments that wish to export products

to the US are required to register with the FDA.

Yet of the 340 foreign tissue establishments registered with

the FDA, only about 7 per cent have an inspection record in the FDA database,

an ICIJ analysis shows. The FDA has never shut one down due to concern over

illicit activities.

The data also shows that about 35 per cent of active

registered US tissue banks have no inspection record in the FDA database.

“When the FDA registers you, all you have to do is fill out a

form and wait for an inspection,” said Dr Duke Kasprisin, the medical director

for seven US tissue banks. “For the first year or two you can function without

having anyone look at you.”

This is backed by the data, which show the typical tissue

bank operates for nearly two years before its first FDA inspection.

“The problem is there is no oversight. The FDA, all they

require is that you have a registration,” said Craig Allred, an attorney

previously involved in litigation against the industry. “Nobody is watching

what is going on.” The FDA and industry players “all point the finger at each

other".

Yet in South Korea, for example, the booming plastic surgery

market uses FDA oversight as a selling point.

In downtown Seoul, the country's capital, Tiara Plastic

Surgery explains that human tissue products “are FDA-approved” and are

therefore safe.

Some medical centres advertise “FDA-approved AlloDerm” ~ a

skin graft made from donated American cadavers ~ for nose enhancement.

Le Do-han, the official in charge of human tissue for the

South Korean FDA, said the country imports 90 per cent of its human-tissue

needs.

Raw tissue is shipped in from the US and Germany. This

tissue, once processed, is often re-exported to Mexico as manufactured goods.

Despite the complicated movements back and forth, Le Do-han

acknowledges that proper tracking hasn't been put in place.

“It is like putting tags on beef, but I don't even know if

that is possible for human tissues because there areso many coming in.”

TEAMING UP

In its US Securities and Exchange Commission filings,

publicly traded RTI provides a glimpse of the company's size and global reach.

In 2011, the company manufactured 500,000 to 600,000

implants and launched 19 new kinds of implants in sports medicine, orthopedics

and other areas. Ninety per cent of the company's implants are made from human

tissue, while 10 per cent come from cows and pigs processed at its German

facility.

RTI requires its human body parts suppliers in the US and

other nations to follow FDA regulations, but the company acknowledges there are

no guarantees.

In 2011 securities filings, RTI said there “can be no

assurances” that “our tissue suppliers will comply with such regulations

intended to prevent communicable disease transmission” or “even if such compliance

is achieved, that our implants have not been or will not be associated with

transmission of disease".

Like many of today's for-profit tissue companies that were

once non-profits, RTI broke away from the non-profit University of Florida

Tissue Bank in 1998.

Internal company files from Tutogen, a Germany medical

products company, show that RTI teamed up with Tutogen as early as September

1999 to help both companies meet their growing needs for raw material by

obtaining human tissue from Eastern Europe.

.

.

The companies both obtained tissue from the Czech Republic.

Tutogen separately obtained tissues from Estonia, Hungary, Russia, Latvia,

Ukraine, and later Slovakia, documents show.

In 2002, allegations surfaced in the Czech media that the

local supplier to RTI and Tutogen was obtaining some tissues there improperly.

Though there is no suggestion that Tutogen or RTI or its employees did anything

improper.

In March 2003, police in Latvia investigated whether

Tutogen's local supplier had removed tissue from about 400 bodies at a state

forensic medical institute without proper consent.

Wood and fabrics, replacing muscle and bone, were put into

the deceased to make it look like they were untouched before burial, local

media reported.

Police eventually charged three employees of the supplier,

but later dismissed the charges when a court ruled that no consent from donors'

families was necessary. Again, there was no suggestion Tutogen acted

improperly.

In 2005, Ukrainian police launched the first of a series of

investigations into the activities of Tutogen's suppliers in that country. The

initial investigation did not lead to criminal charges.

The relationship between Tutogen and RTI, meanwhile, became

even closer in late 2007, when they announced a merger between the two

companies. Tutogen became a subsidiary of RTI in early 2008.

Officials at RTI declined to answer questions from ICIJ

about whether it knew about police investigations of Tutogen's suppliers.

TWO RIBS

In 2008 Ukrainian police launched a new investigation,

looking into allegations that more than 1000 tissues a month were being

illegally recovered at a forensic medical institute at Krivoy Rog and sent, via

a third party, to Tutogen.

Joseph Duesel, the chief prosecutor in Bamberg, said in 2009

that "what the company is doing is approved by the administrative

authority by which it is also monitored. We do not currently see any reason to

initiate investigation proceedings."

Nataliya Grishenko, the judge prosecuting the case, revealed

during subsequent court proceedings that many relatives claimed they had been

tricked into signing consent forms or that their signatures had been forged.

However, the main suspect in the case ~ a Ukrainian doctor ~

died before the court could deliver a verdict. The case died with him.

Tutogen “operates under very strict regulations from German

and Ukrainian authorities as well as other European and American regulatory

authorities”, the company said in a statement while the case was still pending.

“They have been inspected regularly by all of these authorities over their many

years of operation, and Tutogen remains in good standing with all of them.”

Seventeen of Tutogen's Ukrainian suppliers have undergone an

FDA inspection. The inspections are announced, according to protocol, six to

eight weeks in advance.

Only one ~ BioImplant in Kiev ~ received negative feedback.

Among the findings of the 2009 inspection: not all morgues could rely on hot

running water and some sanitation procedures were not followed.

FDA inspectors also identified deficiencies with RTI's

Ukrainian imports when it visited the company's facilities in Florida.

RTI had English translations, but not original autopsy

reports, from its Ukrainian donors, FDA inspectors found during a 2010 audit.

Those were often the only medical documents the company used to determine

whether the donor was healthy, inspectors noted in their report.

The company told inspectors it was illegal under Ukrainian

law to copy the report. But following the inspection it began maintaining the

original Russian-language document along with its English translation.

In 2010 and 2011, FDA inspectors asked RTI to change how it labeled

its imports. The company was obtaining Ukrainian tissue, shipping it to Tutogen

in Germany, and then exporting it to the US as a product of Germany.

While the company agreed to change its policies, there is

some indication that it may have continued labeling some Ukrainian tissue as

German.

This past February police launched a raid as officials at a

regional forensic bureau in Nikolaev Oblast were loading harvested human

tissues into the back of a white minibus. Police footage of the seizure shows

tissue labeled "Tutogen. Made in Germany."

In this case, the security service said forensic officials

had tricked relatives of the dead patients into agreeing to what they thought

was a small amount of tissue harvesting by playing on their pain and grief.

Seized documents ~ blood tests, an autopsy report and labels

written in English and obtained by ICIJ ~ suggested the remains were on their

way to Tutogen.

.

“Two ribs, two Achilles heels, two elbows, two eardrums, two teeth, and so on'' ... a relative holds a picture of Oleksandr Frolov, some of whose body parts were found during a raid by Ukrainian authorities. Photo: Konstantin Chernichkin/Kyiv Post

.

.

“Two ribs, two Achilles heels, two elbows, two eardrums, two teeth, and so on'' ... a relative holds a picture of Oleksandr Frolov, some of whose body parts were found during a raid by Ukrainian authorities. Photo: Konstantin Chernichkin/Kyiv Post

.

Some of the tissue fragments found on the bus came from

35-year-old Oleksandr Frolov, who had died from an epileptic seizure.

“On the way to the cemetery, when we were in the hearse, one

of his feet ~ we noticed that one of the shoes slipped off his foot, which

seemed to be hanging loose,” his mother, Lubov Frolova, told ICIJ.

“When my daughter-in-law touched it, she said that his foot

was empty.”

Later, the police showed her a list of what had been taken

from her son's body.

“Two ribs, two Achilles heels, two elbows, two eardrums, two

teeth, and so on. I couldn't read it till the end, as I felt sick. I couldn't

read it,” she said.

“I heard that [the tissues] were shipped to Germany to be

used for the plastic surgeries and also for donation. I have nothing against

donation, but it should be done according to the law.”

Kateryna Rahulina, whose 52-year-old mother, Olha Dynnyk,

died in September 2011, was shown documents by investigating police. The

documents purported to give her approval for tissue to be taken from her

mother's body.

“I was in shock,” Rahulina said. She never signed the

papers, she said, and it was clear to her that someone had forged her approval.

The forensic bureau in Nikolaev Oblast, where the alleged

incidents happened, was, until recently, one of 20 Ukrainian tissue banks

registered by the FDA.

On the FDA's website the phone number for each of the tissue

banks is the same.

It is Tutogen's phone number in Germany.

International Consortium of Investigative

Journalists

Contributors to this story: Mar Cabra, Alexenia

Dimitrova and Nari Kim.

The International Consortium of Investigative

Journalists is an independent global network of reporters who collaborate on cross-borders

investigative stories. To see video, graphics and more stories in this series,

go to www.icij.org. This story was co-reported

by National Public Radio (USA).

No comments:

Post a Comment

If your comment is not posted, it was deemed offensive.