By Jack Herer

CHAPTER 1 ~

OVERVIEW OF THE HISTORY OF CANNABIS HEMP

For the Purpose of Clarity in this Book:

Explanations or documentations marked with an asterisk (*) are

listed at the end of the related paragraph(s). For brevity, other sources for

facts, anecdotes, histories, studies, etc., are cited in the body of the text.

Numbered footnotes are at the end of each chapter. Reproductions of selected

critical source materials are incorporated into the body of the text or

included in the appendices.

The facts cited herein are generally verifiable in the

Encyclopaedia Britannica, which was printed primarily on paper produced with

cannabis hemp for over 150 years. However, any encyclopedia (no matter how old)

or good dictionary will do for general verification purposes.

CANNABIS SATIVA L.

Also known as: Hemp, cannabis hemp, Indian (India) hemp, true

hemp, muggles, weed, pot, spinach, marijuana, reefer, grass, ganja, bhang, the

kind, dagga, herb, etc., all names for exactly the same plant!

WHAT’S IN A NAME?

(U.S. GEOGRAPHY)

HEMPstead, Long Island; HEMPstead County, Arkansas; HEMPstead,

Texas; HEMPhill, North Carolina, HEMPfield, Pennsylvania, among others, were named

after cannabis growing regions, or after family names derived from hemp

growing.

AMERICAN HISTORICAL NOTES

In 1619, America’s first marijuana law was enacted at Jamestown

Colony, Virginia, “ordering” all farmers to “make tryal of “(grow) Indian

hempseed. More mandatory (must-grow) hemp cultivation laws were enacted in

Massachusetts in 1631, in Connecticut in 1632 and in the Chesapeake Colonies

into the mid-1700s.

Even in England, the much-sought-after prize of full British

citizenship was bestowed by a decree of the crown on foreigners who would grow

cannabis, and fines were often levied against those who refused.

Cannabis hemp was legal tender (money) in most of the Americas

from 1631 until the early 1800s. Why? To encourage American farmers to grow

more.1

You could pay your taxes with cannabis hemp throughout America

for over 200 years.2

You could even be jailed in America for not growing cannabis

during several periods of shortage, e.g., in Virginia between 1763 and 1767.

(Herndon, G.M., Hemp in Colonial Virginia, 1963; The Chesapeake

Colonies, 1954; L.A. Times, August 12, 1981; et al.)

George Washington and Thomas Jefferson grew cannabis on their plantations.

Jefferson,3 while envoy to France, went to great expense, and even considerable

risk to himself and his secret agents, to procure particularly good hempseeds

smuggled illegally into Turkey from China. The Chinese Mandarins (political

rulers) so valued their hemp seed that they made its exportation a capital

offense.

The Chinese character “Ma” was the earliest name for hemp. By

the 10th century, A.D., Ma had become the generic term for fibers of all kinds,

including jute and ramie. By then, the word for hemp had become “Ta-ma” or

“Da-ma” meaning “great hemp.”

The United States Census of 1850 counted 8,327 hemp

“plantations”* (minimum 2,000-acre farms) growing cannabis hemp for cloth,

canvas and even the cordage used for baling cotton. Most of these plantations

were located in the South or in the Border States, primarily because of the

cheap slave labor available prior to 1865 for the labor-intensive hemp

industry.

(U.S. Census, 1850; Allen, James Lane, The Reign of Law, A Tale

of the Kentucky Hemp Fields, MacMillan Co., NY, 1900; Roffman, Roger. Ph.D.,

Marijuana as Medicine, Mendrone Books, WA, 1982.)

*This figure does not include the tens of thousands of smaller

farms growing cannabis, nor the hundreds of thousands if not millions of family

hemp patches in America; nor does it take into account that well into this

century 80% of America’s hemp consumption for 200 years still had to be

imported from Russia, Hungary, Czechoslovakia and Poland, etc..

Benjamin Franklin started one of America’s first paper mills

with cannabis. This allowed America to have a free colonial press without

having to beg or justify the need for paper and books from England.

In addition, various marijuana and hashish extracts were the

first, second or third most-prescribed medicines in the United States from 1842

until the 1890s. Its medicinal use continued legally through the 1930s for

humans and figured even more prominently in American and world veterinary medicines

during this time.

Cannabis extract medicines were produced by Eli Lilly,

Parke-Davis, Tildens, Brothers Smith (Smith Brothers), Squibb and many other

American and European companies and apothecaries. During all this time there

was not one reported death from cannabis extract medicines, and virtually no

abuse or mental disorders reported, except for first-time or novice-users

occasionally becoming disoriented or overly introverted.

(Mikuriya, Tod, M.D., Marijuana Medical Papers, Medi-Comp Press,

CA, 1973; Cohen, Sidney & Stillman, Richard, Therapeutic Potential of

Marijuana, Plenum Press, NY, 1976.)

WORLD HISTORICAL NOTES

“The earliest known woven fabric was apparently of hemp, which

began to be worked in the eighth millennium (8,000-7,000 B.C.).” (The Columbia

History of the World, 1981, page 54.)

The body of literature (i.e., archaeology, anthropology,

philology, economy, history) pertaining to hemp is in general agreement that,

at the very least:

From more than 1,000 years before the time of Christ until 1883

A.D., cannabis hemp, indeed, marijuana was our planet’s largest agricultural

crop and most important industry, involving thousands of products and

enterprises; producing the overall majority of Earth’s fiber, fabric, lighting

oil, paper, incense and medicines. In addition, it was a primary source of

essential food oil and protein for humans and animals.

According to virtually every anthropologist and university in

the world, marijuana was also used in most of our religions and cults as one of

the seven or so most widely used mood-, mind-or pain-altering drugs when taken

as psychotropic, psychedelic (mind-manifesting or -expanding) sacraments.

Almost without exception, these sacred (drug) experiences

inspired our superstitions, amulets, talismans, religions, prayers, and

language codes. (See Chapter10 on “Religions and Magic.”)

(Wasson, R. Gordon, Soma, Divine Mushroom of Immortality;

Allegro, J.M., Sacred Mushroom & the Cross, Doubleday, NY, 1969; Pliny;

Josephus; Herodotus; Dead Sea Scrolls; Gnostic Gospels; the Bible; Ginsberg

Legends Kaballah, c. 1860; Paracelsus; British Museum; Budge; Ency. Britannica,

Pharmacological Cults; Schultes & Wasson, Plants of the Gods; Research of:

R.E. Schultes, Harvard Botanical Dept.; Wm. EmBoden, Cal State U., Northridge;

et al.)

GREAT WARS WERE FOUGHT TO ENSURE THE AVAILABILITY OF HEMP

For example, the primary reason for the War of 1812 (fought by

America against Great Britain) was access to Russian cannabis hemp. Russian

hemp was also the principal reason that Napoleon (our 1812 ally) and his

“Continental Systems” allies invaded Russia in 1812. (See Chapter 11, “The

(Hemp) War of 1812 and Napoleon Invades Russia.”)

In 1942, after the Japanese invasion of the Philippines cut off

the supply of Manila (Abaca) hemp, the U.S. government distributed 400,000

pounds of cannabis seeds to American farmers from Wisconsin to Kentucky, who

produced 42,000 tons of hemp fiber annually until 1946 when the war ended.

WHY HAS CANNABIS HEMP BEEN SO IMPORTANT IN HISTORY?

Because cannabis hemp is, overall, the strongest, most-durable,

longest-lasting natural soft-fiber on the planet. Its leaves and flower tops

(marijuana) were, depending on the culture, the first, second or third

most-important and most-used medicines for two-thirds of the world’s people for

at least 3,000 years, until the turn of the 20th century.

Botanically, hemp is a member of the most advanced plant family

on Earth. It is a dioecious (having male, female and sometimes hermaphroditic,

male and female on same plant), woody, herbaceous annual that uses the sun more

efficiently than virtually any other plant on our planet, reaching a robust 12

to 20 feet or more in one short growing season. It can be grown in virtually

any climate or soil condition on Earth, even marginal ones.

Hemp is, by far,

Earth’s premier, renewable natural resource.

This is why hemp is so very important.

FOOTNOTES:

1. Clark, V.S., History of Manufacture in the United States,

McGraw Hill, NY 1929, Pg. 34.

2. Ibid.

3. Diaries of George Washington; Writings of George Washington,

Letter to Dr. James Anderson, May 26, 1794, vol. 33, p. 433, (U.S. govt. pub.,

1931); Letters to his caretaker, William Pearce, 1795 & 1796; Thomas

Jefferson, Jefferson’s Farm Books; Abel, Ernest, Marijuana: The First 12,000

Years, Plenum Press, NY, 1980; Dr. Michael Aldrich, et al.

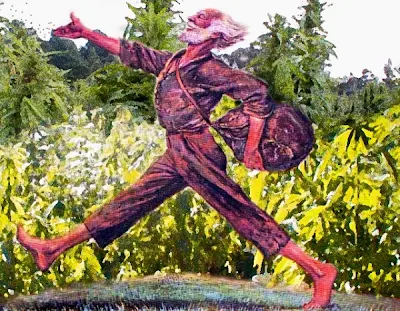

A field of industrial Ukranian hemp.

CHAPTER 2 ~

A BRIEF SUMMARY OF THE USES OF HEMP

If all fossil fuels and their derivatives, as well as trees for

paper and construction were banned in order to save the planet, reverse the

Greenhouse Effect and stop deforestation, then there is only one known annually

renewable natural resource that is capable of providing the overall majority of

the world’s paper and textiles; meeting all of the world’s transportation,

industrial and home energy needs; simultaneously reducing pollution, rebuilding

the soil, and cleaning the atmosphere all at the same time. That substance is

the same one that did it all before, Cannabis Hemp … Marijuana!

SHIPS & SAILORS

From at least the 5th century B.C. until the late-19th

century, 90 percent of all ships’ sails were made from hemp. The other 10 percent

were usually flax or minor fibers like ramie, sisal, jute, abaca, etc.

(Abel, Ernest, Marijuana: The First 12,000 Years, Plenum Press,

1980; Herodotus, Histories, 5th century B.C.; Frazier, Jack, The Marijuana

Farmers, 1972; U.S. Agricultural Index, 1916-1982; USDA film, Hemp for Victory,

1942.)

The word “canvas”1 is the Dutch pronunciation (twice removed,

from French and Latin) of the Greek word “Kannabis.”*

*Kannabis, of the (Hellenized) Mediterranean Basin Greek

language, derived from the Persian and earlier Northern Semitics (Quanuba, Kanabosm,

Cana?, Kanah?) which scholars have now traced back to the dawn of the

6,000-year-old Indo-Semitic European language family base of the Sumerians and

Acadians. The early Sumerian/Babylonian word K(a)N(a)B(a), or Q(a)N(a)B(a) is

one of man’s longest surviving root words.1 (KN means cane and B means two, two

reeds or two sexes.)

In addition to canvas sails, virtually all of the rigging,

anchor ropes, cargo nets, fishing nets, flags, shrouds, and oakum (the main

protection for ships against salt water, used as a sealant between the outer

and inner hull of ships) were made from the stalk of the marijuana plant.

Even the sailors’ clothing, right down to the stitching in the

seamen’s rope-soled and (sometimes) “canvas” shoes, was crafted from cannabis.

An average cargo, clipper, whaler, or naval ship of the line, in the 16th,

17th, 18th, or 19th centuries carried 50 to 100 tons of cannabis hemp rigging,

not to mention the sails, nets, etc., and needed it all replaced every year or

two, due to salt rot. (Ask the U.S. Naval Academy, or see the construction of

the USS Constitution, a.k.a. “Old Ironsides,” Boston Harbor.)

(Abel, Ernest, Marijuana, The First 12,000 Years, Plenum Press,

1980; Ency. Britannica; Magoun, Alexander, The Frigate Constitution, 1928; USDA

film Hemp for Victory, 1942.)

Additionally, the ships’ charts, maps, logs, and Bibles were

made from paper containing hemp fiber from the time of Columbus (15th century)

until the early 1900s in the Western European/American World, and by the

Chinese from the 1st century A.D. on. Hemp paper lasted 50 to 100 times longer

than most preparations of papyrus, and was a hundred times easier and cheaper

to make.

Incredibly, it cost more for a ship’s hempen sails, ropes, etc.

than it did to build the wooden parts.

Nor was hemp use restricted to the briny deep…

TEXTILES & FABRICS

Until the 1880s in America (and until the 20th century in most

of the rest of the world), 80 percent of all textiles and fabrics used for clothing,

tents, bed sheets and linens, rugs, drapes, quilts, towels, diapers, etc., and

even our flag, “Old Glory,” were principally made from fibers of cannabis.

For hundreds, if not thousands of years (until the 1830s),

Ireland made the finest linens and Italy made the world’s finest cloth for

clothing with hemp. The 1893-1910 editions of Encyclopaedia Britannica

indicate, and in 1938, Popular Mechanics estimated that at least half of all

the material that has been called linen was not made from flax, but from

cannabis. Herodotus (c. 450 B.C.) describes the hempen garments made by

the Thracians as equal to linen in fineness and that “none but a very

experienced person could tell whether they were of hemp or flax.”

Although these facts have been almost forgotten, our forebears

were well aware that hemp is softer than cotton, warmer than cotton, more water

absorbent than cotton, has three times the tensile strength of cotton and is

many times more durable than cotton.

In fact, when the patriotic, real-life, 1776 mothers of our

present day blue-blood “Daughters of the American Revolution” (the DAR of

Boston and New England) organized “spinning bees” to clothe Washington’s

soldiers, the majority of the thread was spun from hemp fibers. Were it not for

the historically forgotten (or censored) and currently disparaged marijuana

plant, the Continental Army would have frozen to death at Valley Forge,

Pennsylvania.

The common use of hemp in the economy of the early republic was

important enough to occupy the time and thoughts of our first U.S. Treasury

Secretary Alexander Hamilton, who wrote in a Treasury notice from the 1790s,

“Flax and Hemp: Manufacturers of these articles have so much affinity to each

other, and they are so often blended, that they may with advantage be

considered in conjunction. Sailcloth should have 10% duty…”

(Herndon, G.M., Hemp in Colonial Virginia, 1963; DAR histories;

Able Ernest, Marijuana, the First 12,000 Years; also see the 1985 film

Revolution with Al Pacino.)

The covered wagons went west (to Kentucky, Indiana, Illinois,

Oregon, and California*) covered with sturdy hemp canvas tarpaulins, 2 while

ships sailed around the “Horn” to San Francisco on hemp sails and ropes.

The original, heavy-duty, famous Levi pants were made for the

California ‘49ers out of hempen sailcloth and rivets. This way the pockets

wouldn’t rip when filled with gold panned from the sediment.3

Homespun cloth was almost always spun, by people all over the

world, from fibers grown in the “family hemp patch.” In America, this tradition

lasted from the Pilgrims (1620s) until hemp’s prohibition in the 1930s. In the

1930s, Congress was told by the Federal Bureau of Narcotics that many

Polish-Americans still grew pot in their backyards to make their winter “long johns”

and work clothes, and greeted the agents with shotguns for stealing their next

year’s clothes.

Homespun cloth was almost always spun, by people all over the

world, from fibers grown in the “family hemp patch.” In America, this tradition

lasted from the Pilgrims (1620s) until hemp’s prohibition in the 1930s. In the

1930s, Congress was told by the Federal Bureau of Narcotics that many

Polish-Americans still grew pot in their backyards to make their winter “long johns”

and work clothes, and greeted the agents with shotguns for stealing their next

year’s clothes.

The age and density of the hemp patch influences fiber quality.

If a farmer wanted soft linen-quality fibers he would plant his cannabis close

together. As a rule of thumb, if you plant for medical or recreational use, you

plant one seed per five square yards. When planted for seed: four to five feet

apart.

(Univ. of Kentucky Agricultural. Ext. leaflet, March 1943.)

One-hundred-twenty to 180 seeds to the square yard are planted

for rough cordage or coarse cloth. Finest linen or lace is grown up to 400

plants to the square yard and harvested between 80 to 100 days.

(Farm Crop Reports, USDA international abstracts. CIBA Review

1961-62 Luigi Castellini, Milan Italy.)

By the late 1820s, the new American hand cotton gins (invented

by Eli Whitney in 1793) were largely replaced by European-made “industrial”

looms and cotton gins (“gin” is short for engine), because of Europe’s primary

equipment-machinery-technology (tool and die making) lead over America.

Fifty percent of all chemicals used in American agriculture

today are used in cotton growing. Hemp needs no chemicals and has few weed or

insect enemies ~ except for the U. S. government and the DEA.

For the first time, light cotton clothing could be produced at

less cost than hand retting (rotting) and hand separating hemp fibers to be

handspun on spinning wheels and jennys.4

However, because of its strength, softness, warmth and

long-lasting qualities, hemp continued to be the second most-used natural fiber

until the 1930s. In case you’re wondering, there is no THC or “high” in hemp

fiber. That’s right; you can’t smoke your shirt! In fact, attempting to smoke

hemp fabric, or any fabric, for that matter, could be fatal!

After the 1937 Marijuana Tax law, new DuPont “plastic fibers,”

under license since 1936 from the German company I.G. Farben (patent surrenders

were part of Germany’s World War I reparation payments to America), replaced

natural hempen fibers. (Some 30% of I.G. Farben, under Hitler, was owned and

financed by America’s DuPont.) DuPont also introduced Nylon (invented in 1935)

to the market after they’d patented it in 1938.

(Colby, Jerry, DuPont Dynasties, Lyle Stewart, 1984.)

Finally, it must be noted that approximately 50 percent of all

chemicals used in American agriculture today are used in cotton growing. Hemp

needs no chemicals and has few weed or insect enemies, except for the U.S.

government and the DEA.

(Cavender, Jim, Professor of Botany, Ohio University,

“Authorities Examine Pot Claims,” Athens News, November 16, 1989.)

FIBER & PULP PAPER

Until 1883, from 75-90 percent of all paper in the world was

made with cannabis hemp fiber, including that for books, Bibles, maps, paper money,

stocks and bonds, newspapers, etc. The Gutenberg Bible (in the 15th century);

Pantagruel and the Herb pantagruelion, Rabelais (16th century); King James

Bible (17th century); Thomas Paine’s pamphlets, The Rights of Man, Common

Sense, The Age of Reason (18th century); the works of Fitz Hugh Ludlow, Mark

Twain, Victor Hugo, Alexander Dumas; Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland (19th

century); and just about everything else was printed on hemp paper.

The first draft of the Declaration of Independence (June 28,

1776) was written on Dutch (hemp) paper, as was the second draft completed on

July 2, 1776. This was the document actually agreed to on that day and

announced and released on July 4, 1776. On July 19, 1776, Congress ordered the

Declaration be copied and engrossed on parchment (a prepared animal skin) and

this was the document actually signed by the delegates on August 2, 1776.

Hemp paper lasted 50 to 100 times longer than most preparations

of papyrus, and was a hundred times easier and cheaper to make.

What we (the colonial Americans) and the rest of the world used

to make all our paper from was the discarded sails and ropes sold by ship

owners as scrap for recycling into paper. The rest of our paper came from our

worn-out clothes, sheets, diapers, curtains and rags, made primarily from hemp

and sometimes flax, then sold to scrap dealers. Hence the term “rag paper.”

Our ancestors were too thrifty to just throw anything away, so,

until the 1880s, any remaining scraps and clothes were mixed together and

recycled into paper. Rag paper, containing hemp fiber, is the highest quality

and longest lasting paper ever made. It can be torn when wet, but returns to

its full strength when dry. Barring extreme conditions, rag paper remains

stable for centuries. It will almost never wear out. Many U.S. government

papers were written, by law, on hempen “rag paper” until the 1920s.5

It is generally believed by scholars that the early Chinese

knowledge, or art, of hemp paper making (1st century A.D., 800 years before

Islam discovered how, and 1,200 to 1,400 years before Europe) was one of the

two chief reasons that Oriental knowledge and science were vastly superior to

that of the West for 1,400 years. Thus, the art of long-lasting hemp

papermaking allowed the Orientals’ accumulated knowledge to be passed on, built

upon, investigated, refined, challenged and changed, for generation after

generation (in other words, cumulative and comprehensive scholarship).

The other reason that Oriental knowledge and science sustained

superiority to that of the West for 1,400 years was that the Roman Catholic

Church forbade reading and writing for 95% of Europe’s people; in addition,

they burned, hunted down, or prohibited all foreign or domestic books,

including their own Bible!, for over 1,200 years under the penalty and

often-used punishment of death. Hence, many historians term this period “The

Dark Ages” (476 A.D.–1000 A.D., or even until the Renaissance). (See Chapter 10

on Sociology.)

ROPE, TWINE & CORDAGE

Virtually every city and town (from time out of mind) in the

world had an industry making hemp rope.6 Russia, however, was the world’s

largest producer and best-quality manufacturer, supplying 80% of the Western

world’s hemp from 1640 until 1940.

Virtually every city and town (from time out of mind) in the

world had an industry making hemp rope.6 Russia, however, was the world’s

largest producer and best-quality manufacturer, supplying 80% of the Western

world’s hemp from 1640 until 1940.

Thomas Paine outlined four essential natural resources for the

new nation in Common Sense (1776): “cordage, iron, timber and tar.”

Chief among these was hemp for cordage. He wrote, “Hemp

flourishes even to rankness, we do not want for cordage.” Then he went on to

list the other essentials necessary for war with the British navy: cannons,

gun-powder, etc.

From 70-90% of all rope, twine, and cordage was made from hemp

until 1937. It was then replaced mostly by petrochemical fibers (owned

principally by DuPont under license from Germany’s I.G. Farben Corporation

patents) and by Manila (Abaca) Hemp, with steel cables often intertwined for

strength, brought in from our “new” far-western Pacific Philippines possession,

seized from Spain as reparation for the Spanish American War in 1898.

ART CANVAS

Hemp is the perfect archival medium.7

The paintings of Van Gogh, Gainsborough, Rembrandt, etc., were

primarily painted on hemp canvas, as were practically all canvas paintings.

A strong, lustrous fiber, hemp withstands heat, mildew, and

insects and is not damaged by light. Oil paintings on hemp and/or flax canvas

have stayed in fine condition for centuries.

For thousands of years, virtually all good paints and varnishes

were made with hempseed oil and/or linseed oil.

PAINTS & VARNISHES

For instance, in 1935 alone, 116 million pounds (58,000 tons*)

of hempseed were used in America just for paint and varnish. The hemp drying

oil business went principally to DuPont petro-chemicals.8

National Institute of Oilseed Products congressional testimony

against the 1937 Marijuana Transfer Tax Law. As a comparison, consider that the

U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), along with all America’s state and

local police agencies, claim to have seized for all of 1996, 700+ tons of

American-grown marijuana: seed, plant, root, dirt clump and all. Even the DEA

itself admits that 94 to 97 percent of all marijuana/hemp plants that have been

seized and destroyed since the 1960s were growing completely wild and could not

have been smoked as marijuana.

Congress and the Treasury Department were assured through secret

testimony given by DuPont in 1935-37 directly to Herman Oliphant, Chief Counsel

for the Treasury Dept., that hempseed oil could be replaced with synthetic

petrochemical oils made principally by DuPont.

Oliphant was solely responsible for drafting the Marijuana Tax

Act that was submitted to Congress.9 (See complete story in Chapter 4, “The

Last Days of Legal Cannabis.”)

Until about 1800, hempseed oil was the most consumed lighting

oil in America and the world. From then until the 1870s, it was the second most

consumed lighting oil, exceeded only by whale oil.

LIGHTING OIL

Hempseed oil lit the lamps of the legendary Aladdin, Abraham the

prophet, and in real life, Abraham Lincoln.

It was the brightest lamp oil.

Hempseed oil for lamps was replaced by petroleum, kerosene,

etc., after the 1859 Pennsylvania oil discovery and John D. Rockefeller’s

1870-on national petroleum stewardship. (See Chapter 9 on “Economics.”) In

fact, the celebrated botanist Luther Burbank stated, “The seed [of cannabis] is

prized in other countries for its oil, and its neglect here illustrates the

same wasteful use of our agricultural resources.”

(Burbank, Luther, How Plants Are Trained To Work for Man, Useful

Plants, P. F. Collier & Son Co., NY, Vol. 6, pg. 48.)

The "Eco Elise" car made primarily of hemp products and runs on hemp oil. This car is produced by Lotus, people who know their vehicles. They call it "a new type of green car".

The "Eco Elise" car made primarily of hemp products and runs on hemp oil. This car is produced by Lotus, people who know their vehicles. They call it "a new type of green car".

BIOMASS ENERGY

In the early 1900s, Henry Ford and other futuristic, organic,

engineering geniuses recognized (as their intellectual, scientific heirs still

do today) an important point, that up to 90% of all fossil fuel used in the

world today (coal, oil, natural gas, etc.) should long ago have been replaced

with biomass such as: cornstalks, cannabis, waste paper and the like.

Biomass can be converted to methane, methanol or gasoline at a fraction of the current cost of oil, coal, or nuclear energy, especially when environmental costs are factored in, and its mandated use would end acid rain, end sulfur-based smog, and reverse the Greenhouse Effect on our planet, right now! Government and oil and coal companies, etc., will insist that burning biomass fuel is no better than using up our fossil fuel reserves, as far as pollution goes; but this is patently untrue.

Biomass can be converted to methane, methanol or gasoline at a fraction of the current cost of oil, coal, or nuclear energy, especially when environmental costs are factored in, and its mandated use would end acid rain, end sulfur-based smog, and reverse the Greenhouse Effect on our planet, right now! Government and oil and coal companies, etc., will insist that burning biomass fuel is no better than using up our fossil fuel reserves, as far as pollution goes; but this is patently untrue.

Why? Because, unlike fossil fuel, biomass comes from living (not

extinct) plants that continue to remove carbon dioxide pollution from our

atmosphere as they grow, through photosynthesis. Furthermore, biomass fuels do

not contain sulfur.

This can be accomplished if hemp is grown for biomass and then

converted through pyrolysis (charcoalizing) or biochemical composting into

fuels to replace fossil fuel energy products. Remarkably, when considered on a

planet-wide, climate-wide, soil-wide basis, cannabis is at least four and possibly

many more times richer in sustainable, renewable biomass/cellulose potential

than its nearest rivals on the planet, cornstalks, sugarcane, kenaf, trees,

etc.

This can be accomplished if hemp is grown for biomass and then

converted through pyrolysis (charcoalizing) or biochemical composting into

fuels to replace fossil fuel energy products. Remarkably, when considered on a

planet-wide, climate-wide, soil-wide basis, cannabis is at least four and possibly

many more times richer in sustainable, renewable biomass/cellulose potential

than its nearest rivals on the planet, cornstalks, sugarcane, kenaf, trees,

etc.

(Solar Gas, 1980; Omni, 1983: Cornell University; Science

Digest, 1983: etc.)

Also see Chapter 9 on “Economics.”

One product of pyrolysis, methanol, is used today by most race

cars and was used by American farmers and auto drivers routinely with

petroleum/methanol options starting in the 1920s, through the 1930s, and even

into the mid-1940s to run tens of thousands of auto, farm and military vehicles

until the end of World War II.

Methanol can even be converted to a high-octane lead-free

gasoline using a catalytic process developed by Georgia Tech University in

conjunction with Mobil Oil Corporation.

MEDICINE

From 1842 through the 1890s, extremely strong marijuana (then

known as cannabis extractums) and hashish extracts, tinctures and elixirs were

routinely the second and third most-used medicines in America for humans (from

birth, through childhood, to old age) and in veterinary medicine until the

1920s and longer.

(See Chapter 6 on “Medicine,” and Chapter 13 on the “19th

Century.”)

As stated earlier, for at least 3,000 years, prior to 1842,

widely varying marijuana extracts (buds, leaves, roots, etc.) were the most

commonly used and widely accepted medicines in the world for the majority of

mankind’s illnesses.

However, in Western Europe, the Roman Catholic Church forbade

use of cannabis or any medical treatment, except for alcohol or bloodletting,

for 1200-plus years.

(See Chapter 10 on “Sociology.”)

The U.S. Pharmacopoeia indicated that cannabis should be used

for treating such ailments as: fatigue, fits of coughing, rheumatism, asthma,

delirium tremens, migraine headaches and the cramps and depressions associated

with menstruation.

(Professor William EmBoden, Professor of Narcotic Botany,

California State University, Northridge.)

Queen Victoria used cannabis resins for her menstrual cramps and

PMS, and her reign (1837-1901) paralleled the enormous growth of the use of

Indian cannabis medicine in the English-speaking world.

In the 20th century, cannabis research has demonstrated

therapeutic value and complete safety in treating many health problems including

asthma, glaucoma, nausea, tumors, epilepsy, infection, stress, migraines,

anorexia, depression, rheumatism, arthritis, Alzheimer’s disease and herpes.

(See Chapter 7, “Therapeutic Uses of Cannabis.”)

FOOD OILS & PROTEIN

Hempseed was regularly used in porridge, soups, and gruels by

virtually all the people of the world up until this century. Monks were

required to eat hempseed dishes three times a day, to weave their clothes with

it and to print their Bibles on paper made with its fiber.

Hempseed was regularly used in porridge, soups, and gruels by

virtually all the people of the world up until this century. Monks were

required to eat hempseed dishes three times a day, to weave their clothes with

it and to print their Bibles on paper made with its fiber.

(See Rubin, Dr. Vera, “Research Institute for the Study Of Man;”

Eastern Orthodox Church; Cohen & Stillman, Therapeutic Potential of

Marijuana, Plenum Press, 1976; Abel, Ernest, Marijuana, The First 12,000 Years,

Plenum Press, NY, 1980; Encyclopedia Britannica.)

Hempseed can be pressed for its highly nutritious vegetable oil,

which contains the highest amount of essential fatty acids in the plant

kingdom. These essential oils are responsible for our immune responses and

clear the arteries of cholesterol and plaque.

The byproduct of pressing the oil from the seed is the highest

quality protein seed cake. It can be sprouted (malted) or ground and baked into

cakes, breads and casseroles. Marijuana seed protein is one of mankind’s

finest, most complete and available-to-the-body vegetable proteins. Hempseed is

the most complete single food source for human nutrition.

(See discussion of edestins and essential fatty acids, Chapter

8.)

Hempseed was, until the 1937 prohibition law, the world’s

number-one bird seed, for both wild and domes-tic birds. It was their favorite*

of any seed food on the planet; four million pounds of hempseed for songbirds

were sold at retail in the U.S. in 1937. Birds will pick hempseeds out and eat

them first from a pile of mixed seed. Birds in the wild live longer and breed

more with hempseed in their diet, using the oil for their feathers and their

overall health.

(More in Chapter 8, “Hemp as a Basic World Food.”)

Congressional testimony, 1937: “Song birds won’t sing without it,”

the bird food companies told Congress. Result: sterilized cannabis seeds

continue to be imported into the U.S. from Italy, China and other countries.

Hempseed produces no observable high for humans or birds. Only

the minutest traces of THC are in the seed. Hempseed is also the favorite fish

bait in Europe. Anglers buy pecks of hempseed at bait stores, and then throw

handfuls into rivers and ponds. Fish come thrashing for the hempseed and are

caught by hook. No other bait is as effective, making hempseed generally the

most desirable and most nutritious food for humans, birds and fish.

(Jack Herer’s personal research in Europe.) (Frazier, Jack, The

Marijuana Farmers, Solar Age Press, New Orleans, LA, 1972)

BUILDING MATERIALS & HOUSING

Because one acre of hemp produces as much cellulose fiber pulp

as 4.1 acres of trees,* hemp is the perfect material to replace trees for

pressed board, particle board and for concrete construction molds.

*Dewey & Merrill, Bulletin #404, United States Dept. of

Agricultural., 1916.

Practical, inexpensive fire-resistant construction material,

with excellent thermal and sound-insulating qualities, is made by heating and

compressing plant fibers to create strong construction paneling, replacing dry

wall and plywood. William B. Conde of Conde’s Redwood Lumber, Inc. near Eugene,

OR, in conjunction with Washington State University (1991–1993), has

demonstrated the superior strength, flexibility, and economy of hemp composite

building materials compared to wood fiber, even as beams.

Isochanvre, a rediscovered French building material made from

hemp hurds mixed with lime, actually petrifies into a mineral state and lasts

for many centuries. Archeologists have found a bridge in the south of France,

from the Merovingian period (500–751 A.D.), built with this process. (See

Chènevotte habitat of René, France in Appendix I.)

Hemp has been used throughout history for carpet backing. Hemp

fiber has potential in the manufacture of strong, rot resistant carpeting,

eliminating the poisonous fumes of burning synthetic materials in a house or

commercial fire, along with allergic reactions associated with new synthetic

carpeting.

Plastic plumbing pipe (PVC pipes) can be manufactured using

renewable hemp cellulose as the chemical feedstocks, replacing non-renewable

coal or petroleum-based chemical feedstocks.

So we can envision a house of the future built, plumbed, painted

and furnished with the world’s number-one renewable resource, hemp.

SMOKING, LEISURE & CREATIVITY

The American Declaration of Independence recognizes the

“inalienable rights” of “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.”

Subsequent court decisions have inferred the rights to privacy and choice from

this, the U.S. Constitution and its Amendments.

The American Declaration of Independence recognizes the

“inalienable rights” of “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.”

Subsequent court decisions have inferred the rights to privacy and choice from

this, the U.S. Constitution and its Amendments.

Many artists and writers have used cannabis for creative

stimulation, from the writers of the world’s religious masterpieces to our most

irreverent satirists. These include Lewis Carroll and his hookah-smoking

caterpillar in Alice in Wonderland, plus Victor Hugo and Alexander Dumas; such

jazz greats as Louis Armstrong, Cab Calloway, Duke Ellington and Gene Krupa;

and the pattern continues right up to modern-day artists and musicians such as

the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, the Eagles, the Doobie Brothers, Bob Marley, Jefferson

Airplane, Willie Nelson, Buddy Rich, Country Joe & the Fish, Joe Walsh,

David Bowie, Iggy Pop, Lola Falana, Hunter S. Thompson, Peter Tosh, the

Grateful Dead, Cypress Hill, Sinead O’Connor, Black Crowes, Snoop Dogg, Los

Marijuanos, etc.

Of course, smoking marijuana only enhances creativity for some

and not for others.

But throughout history, various prohibition and “temperance”

groups have attempted and occasionally succeeded in banning the preferred

relaxational substances of others, like alcohol, tobacco or cannabis.

But throughout history, various prohibition and “temperance”

groups have attempted and occasionally succeeded in banning the preferred

relaxational substances of others, like alcohol, tobacco or cannabis.

Abraham Lincoln responded to this kind of repressive mentality

in December, 1840, when he said “Prohibition/goes beyond the bounds of reason

in that it attempts to control a man’s appetite by legislation and makes a crime

out of things that are not crimes. A prohibition law strikes a blow at the very

principles upon which our government was founded.”

ECONOMIC STABILITY, PROFIT & FREE TRADE

We believe that in a competitive market, with all facts known,

people will rush to buy long-lasting, biodegradable “Pot Tops” or “Mary Jeans,”

etc., made from a plant without pesticides or herbicides.

It’s time we put capitalism to the test and let the unrestricted

market of supply and demand, as well as “Green” ecological consciousness,

decide the future of the planet.

A cotton shirt in 1776 cost $100 to $200, while a hemp shirt

cost .50 cents to $1. By the 1830s, cooler, lighter cotton shirts were on

par in price with the warmer, heavier, hempen shirts, providing a competitive choice.

People were able to choose their garments based upon the

particular qualities they wanted in a fabric. Today we have no such choice.

The role of hemp and other natural fibers should be determined

by the market of supply and demand and personal tastes and values, not by the

undue influence of prohibition laws, federal subsidies and huge tariffs that

keep the natural fabrics from replacing synthetic fibers.

Seventy years of government suppression of information has

resulted in virtually no public knowledge of the incredible potential of the

hemp fiber or its uses.

By using 100 percent hemp or mixing hemp with organic cotton,

you will be able to pass on your shirts, pants and other clothing to your

grandchildren. Intelligent spending could essentially replace the use of

petrochemical synthetic fibers such as nylon and polyester with tougher,

cheaper, cool, absorbent, breathing, biodegradable, natural fibers.

China, Italy and Eastern European countries such as Hungary,

Romania, Czechoslovakia, Poland, and Russia currently make millions of dollars

worth of sturdy hemp and hemp/cotton textiles, and could be making billions of

dollars worth annually.

These countries build upon their traditional farming and weaving

skills, while the U.S. tries to force the extinction of this plant to prop up

destructive synthetic technologies.

Even cannabis/cotton blend textiles were still not cleared for

direct sale in the U.S. until 1991. The Chinese, for instance, were forced by

tacit agreement to send us inferior ramie /cottons.

(National Import/Export Textile Company of Shanghai, personal

communication with author, April and May 1983.)

As the 1990 edition of Emperor went to press, garments

containing at least 55 percent cannabis hemp arrived from China and Hungary. In

1992, as we went to press, many different grades of 100% hemp fabric had

arrived directly from China and Hungary. Now, hemp fabric is in booming demand

all over the world, arriving from Romania, Poland, Italy, Germany, et al. Hemp

was recognized as the hottest fabric of the 1990s by Rolling Stone, Time,

Newsweek, Paper, Detour, Details, Mademoiselle, The New York Times, The Los

Angeles Times, Der Spiegel, ad infinitum. All have run, over and over again,

major stories on industrial and nutritional hemp.

Additionally, hemp grown for biomass could fuel a

trillion-dollar per year energy industry, while improving air quality and

distributing the wealth to rural areas and their surrounding communities, and

away from centralized power monopolies. More than any other plant on Earth,

hemp holds the promise of a sustainable ecology and economy.

FOOTNOTES:

1. Oxford English Dictionary; Encyclopedia Britannica, 11th

edition, 1910; U.S.D.A. film, Hemp for Victory, 1942.

2. Ibid.

3. Levi-Strauss & Company of San Francisco, CA, author’s

personal communication with Gene McClaine, 1985.

4. Ye Olde Spinning Jennys and Wheels were principally used for

fiber in this order: cannabis hemp, flax, wool, cotton, and so forth.

5. Frazier, Jack, The Marijuana Farmers, Solar Age Press, New

Orleans, LA, 1974; U.S. Library of Congress; National Archives; U.S. Mint; etc.

6. Adams, James T., editor, Album of American History, Charles

Scribner’s Sons, NY, 1944, pg. 116.

7. Frazier, Jack, The Marijuana Farmers, Solar Age Press, New

Orleans, LA, 1974; U.S. Library of Congress; National Archives.

8. Sloman, Larry, Reefer Madness, Grove Press, New York, NY,

1979, pg. 72.

9. Bonnie, Richard and White bread, Charles, The Marijuana

Conviction, Univ. of Virginia Press, 1974.

WHEN HEMP SAVED GEORGE BUSH’S LIFE

One more example of the importance of hemp: Five years after

cannabis hemp was outlawed in 1937, it was promptly reintroduced for the World War

II effort in 1942.

So, when the young pilot, George Bush, baled out of his burning

airplane after a battle over the Pacific, little did he know:

Yet Bush has spent a good deal of his career eradicating the cannabis plant and enforcing laws to make certain that no one will learn this information – possibly including himself. . .~ Parts of his aircraft engine were lubricated with cannabis hempseed oil;~ 100 percent of his life-saving parachute webbing was made from U.S. grown cannabis hemp;~ Virtually all the rigging and ropes of the ship that pulled him in were made of cannabis hemp.~ The fire hoses on the ship (as were those in the schools he had attended) were woven from cannabis hemp; and,~ Finally, as young George Bush stood safely on the deck, his shoes’ durable stitching was of cannabis hemp, as it is in all good leather and military shoes to this day.

(USDA film, Hemp for Victory, 1942; U. of KY Agricultural Ext.

Service Leaflet 25, March 1943; Galbraith, Gatewood, Kentucky Marijuana

Feasibility Study, 1977.)

THE BATTLE OF BULLETIN 404

THE SETTING

In 1917, the world was battling World War I. In this country,

industrialists, just beset with the minimum wage and graduated income tax, were

sent into a tailspin. Progressive ideals were lost as the United States took

its place on the world stage in the struggle for commercial supremacy. It is

against this backdrop that the first 20th century hemp drama was played.

THE PLAYERS

The story begins in 1916, soon after the release of USDA

Bulletin 404 (see page 24). Near San Diego, California, a 50-year-old German

immigrant named George Schlichten had been working on a simple yet brilliant

invention. Schlichten had spent 18 years and $400,000 on the decorticator, a

machine that could strip the fiber from nearly any plant, leaving the pulp

behind. To build it, he had developed an encyclopedic knowledge of fibers and

paper making. His desire was to stop the felling of forests for paper, which he

believed to be a crime. His native Germany was well advanced in forestry and

Schlichten knew that destroying forests meant destroying needed watersheds.

Henry Timken, a wealthy industrialist and inventor of the roller

bearing got wind of Schlichten’s invention and went to meet the inventor in

February of 1917. Timken saw the decorticator as a revolutionary discovery that

would improve conditions for mankind. Timken offered Schlichten the chance to

grow 100 acres of hemp on his ranch in the fertile farmlands of Imperial

Valley, California, just east of San Diego, so that Schlichten could test his

invention.

Shortly thereafter, Timken met with the newspaper giant E.W.

Scripps, and his long-time associate Milton McRae, at Miramar, Scripps’ home in

San Diego. Scripps, then 63, had accumulated the largest chain of newspapers in

the country. Timken hoped to interest Scripps in making newsprint from hemp

hurds.

Turn-of-the-century newspaper barons needed huge amounts of

paper to deliver their swelling circulations. Nearly 30% of the four million

tons of paper manufactured in 1909 was news-print; by 1914 the circulation of

daily newspapers had increased by 17% over 1909 figures to over 28 million

copies.1 By 1917, the price of newsprint was rapidly rising, and McRae, who had

been investigating owning a paper mill since 1904,2 was concerned.

.

SOWING THE SEEDS

In May, after further meetings with Timken, Scripps asked McRae

to investigate the possibility of using the decorticator in the manufacture of

newsprint.

McRae quickly became excited about the plan. He called the

decorticator “a great invention. . . [which] will not only render great service

to this country, but it will be very profitable financially. . . . [it] may

revolutionize existing conditions.” On August 3, as harvest time neared, a

meeting was arranged between Schlichten, McRae, and newspaper manager Ed Chase.

Without Schlichten’s knowledge, McRae had his secretary record

the three-hour meeting stenographically. The resulting document, the only known

record of Schlichten’s voluminous knowledge found to date, is reprinted fully

in Appendix I.

Schlichten had thoroughly studied many kinds of plants used for

paper, among them corn, cotton, yucca, and Espana baccata. Hemp, it seemed, was

his favorite: “The hemp hurd is a practical success and will make paper of a

higher grade than ordinary news stock,” he stated. His hemp paper was even

better than that produced for USDA Bulletin 404, he claimed, because the

decorticator eliminated the retting process, leaving behind short fibers and a

natural glue that held the paper together. At 1917 levels of hemp production

Schlichten anticipated making 50,000 tons of paper yearly at a retail price of

$25 a ton. This was less than 50% of the price of newsprint at the time! And

every acre of hemp turned to paper, Schlichten added, would preserve five acres

of forest.

McRae was very impressed by Schlichten. The man who dined with

presidents and captains of industry wrote to Timken, “I was to say without equivocation

that Mr. Schlichten impressed me as being a man of great intellectuality and

ability; and so far as I can see, he has created and constructed a wonderful

machine.” He assigned Chase to spend as much time as he could with Schlichten

and prepare a report.

HARVEST TIME

By August, after only three months of growth, Timken’s hemp crop

had grown to its full height – 14 feet!, and he was highly optimistic about its

prospects. He hoped to travel to California to watch the crop being

decorticated, seeing himself as a benefactor to mankind who would enable people

to work shorter hours and have more time for “spiritual development.” Scripps,

on the other hand, was not in an optimistic frame of mind. He had lost faith in

a government that he believed was leading the country to financial ruin because

of the war, and that would take 40% of his profits in income tax.

In an August 14 letter to his sister, Ellen, he said: “When Mr.

McRae was talking to me about the increase in the price of white paper that was

pending, I told him I was just fool enough not to be worried about a thing of

that kind.” The price of paper was expected to rise 50%, costing Scripps his

entire year’s profit of $1,125,000! Rather than develop a new technology, he

took the easy way out: the Penny Press Lord simply planned to raise the price

of his papers from one cent to two cents.

THE DEMISE

On August 28, Ed Chase sent his full report to Scripps and

McRae. The younger man also was taken with the process: “I have seen a

wonderful, yet simple, invention. I believe it will revolutionize many of the

processes of feeding, clothing, and supplying other wants of mankind.”

Chase witnessed the decorticator produce seven tons of hemp

hurds in two days. At full production, Schlichten anticipated each machine

would produce five tons per day. Chase figured hemp could easily supply

Scripps’ West Coast newspapers, with leftover pulp for side businesses. He

estimated the newsprint would cost between $25 and $35 per ton, and proposed

asking an East Coast paper mill to experiment for them.

McRae, however, seems to have gotten the message that his boss

was no longer very interested in making paper from hemp. His response to

Chase’s report is cautious: “Much will be determined as to the practicability

by the cost of transportation, manufacture, etc., etc., which we cannot

ascertain without due investigation.” Perhaps when his ideals met with the hard

work of developing them, the semi-retired McRae backed off.

By September, Timken’s crop was producing one ton of fiber and

four tons of hurds per acre, and he was trying to interest Scripps in opening a

paper mill in San Diego. McRae and Chase traveled to Cleveland and spent two

hours convincing Timken that, while hemp hurds were usable for other types of

paper, they could not be made into newsprint cheaply enough. Perhaps the

eastern mill at which they experimented wasn’t encouraging – after all, it was

set up to make wood pulp paper.

By this time Timken, too, was hurt by the wartime economy. He

expected to pay 54% income tax and was trying to borrow $2 million at 10%

interest to retool for war machines. The man who a few weeks earlier could not

wait to get to California no longer expected to go west at all that winter. He

told McRae, “I think I will be too damn busy in this section of the country

looking after business.”

The decorticator resurfaced in the 1930s, when it was touted as

the machine that would make hemp a “Billion Dollar Crop” in articles in

Mechanical Engineering and Popular Mechanics.* (Until the 1993 edition of The

Emperor, the decorticator was believed to be a new discovery at that time.)

Once again, the burgeoning hemp industry was halted, this time by the Marijuana

Tax Act of 1937.

• Ellen Komp

A fuller account of the story may be found in the Appendix.

FOOTNOTES:

1. World Almanac, 1914, p. 225; 1917

2. Forty Years in Newspaperdom, Milton McRae, 1924 Brentano’s NY

3. Scripps Archives, University of Ohio, Athens, and Ellen

Browning Scripps Archives, Denison Library, Claremont College, Claremont, CA

WHY NOT USE HEMP TO REVERSE THE GREENHOUSE EFFECT & SAVE THE WORLD?

In early 1989, Jack Herer and Maria Farrow put this question to

Steve Rawlings, the highest ranking officer in the U.S. Department of

Agriculture (who was in charge of reversing the Greenhouse Effect), at the USDA

world research facility in Beltsville, Maryland.

First, we introduced ourselves and told him we were writing for

Green political party newspapers. Then we asked Rawlings, “If you could have

any choice, what would be the ideal way to stop or reverse the Greenhouse

Effect?”

He said, “Stop cutting down trees and stop using fossil fuels.”

“Well, why don’t we?”

“There’s no viable substitute for wood for paper, or for fossil

fuels.”

“Why don’t we use an annual plant for paper and for biomass to

make fuel?”

“Well, that would be ideal,” he agreed. “Unfortunately there is

nothing you can use that could produce enough materials.”

“Well, what would you say if there was such a plant that could

substitute for all wood pulp paper, all fossil fuels, would make most of our

fibers naturally, make everything from dynamite to plastic, grows in all 50

states and that one acre of it would replace 4.1 acres of trees, and that if

you used about 6% of the U.S. land to raise it as an energy crop, even on our

marginal lands, this plant would produce all 75 quadrillion billion BTUs needed

to run America each year? Would that help save the planet?”

“That would be ideal. But there is no such plant.”

“We think there is.”

“Yeah? What is it?”

“Hemp.”

“Hemp!” he mused for a moment. “I never would have thought of

it. You know, I think you’re right. Hemp could be the plant that could do it.

Wow! That’s a great idea!”

We were excited as we outlined this information and delineated

the potential of hemp for paper, fiber, fuel, food, paint, etc., and how it

could be applied to balance the world’s ecosystems and restore the atmosphere’s

oxygen balance with almost no disruption of the standard of living to which

most Americans have become accustomed.

In essence, Rawlings agreed that our information was probably

correct and could very well work.

He said, “It’s a wonderful idea, and I think it might work. But,

of course, you can’t use it.”

“You’re kidding!” we responded. “Why not?”

“Well, Mr. Herer, did you know that hemp is also marijuana?”

“Yes, of course I know, I’ve been writing about it for about 40

hours a week for the past 17 years.”

“Well, you know marijuana’s illegal, don’t you? You can’t use

it.”

“Not even to save the world?”

“No. It’s illegal”, he sternly informed me. “You cannot use

something illegal.”

“Not even to save the world?” we asked, stunned.

“No, not even to save the world. It’s illegal. You can’t use it.

Period.”

“Don’t get me wrong. It’s a great idea,” he went on, “but

they’ll never let you do it.”

“Why don’t you go ahead and tell the Secretary of Agriculture

that a crazy man from California gave you documentation that showed hemp might

be able to save the planet and that your first reaction is that he might be

right and it needs some serious study. What would he say?” “Well, I don’t think

I’d be here very long after I did that. After all, I’m an officer of the

government.” “Well, why not call up the information on your computer at your

own USDA library. That’s where we got the information in the first place.”

He said, “I can’t sign out that information.”

“Well, why not? We did.”

“Mr. Herer, you’re a citizen. You can sign out for anything you

want. But I am an officer of the Department of Agriculture. Someone’s going to

want to know why I want all this information. And then I’ll be gone.”

Finally, we agreed to send him all the information we got from

the USDA library, if he would just look at it.

He said he would, but when we called back a month later, he said

that he still had not opened the box that we sent him and that he would be

sending it back to us unopened because he did not want to be responsible for

the information, now that the Bush Administration was replacing him with its

own man.

We asked him if he would pass on the information to his

successor, and he replied, “Absolutely not.”

In May 1989, we had virtually the same conversation and result

with his cohort, Dr. Gary Evans of the U.S. Department of Agriculture and

Science, the man in charge of stopping the global warming trend.

In the end, he said, “If you really want to save the planet with

hemp, then you [hemp/marijuana activists] would find a way to grow it without

the narcotic (sic) top and then you can use it.”

This is the kind of frightened (and frightening)

irresponsibility we’re up against in our government.

.

CHAPTER 3 ~ POPULAR MECHANICS MAGAZINE, FEBRUARY 1938, "THE MOST PROFITABLE & DESIRABLE CROP THAT CAN BE GROWN”

.

Modern technology was about to be applied to hemp production,

making it the number-one agricultural resource in America. Two of the most

respected and influential journals in the nation, Popular Mechanics and

Mechanical Engineering, forecast a bright future for American hemp. Thousands

of new products creating millions of new jobs would herald the end of the Great

Depression. Instead hemp was persecuted, outlawed and forgotten at the bidding

of W. R. Hearst, who branded hemp the “Mexican killer weed, marihuana.”

As early as 1901 and continuing to 1937, the U.S. Department of

Agriculture repeatedly predicted that, once machinery capable of harvesting, As

you will see in these articles, the newly mechanized stripping and separating

the fiber from the pulp was cannabis hemp industry was in its infancy, but well

on invented or engineered, hemp would again be America’s number-one farm crop.

The introduction of G. W. decorticator in 1917 nearly fulfilled this prophesy.

The prediction was reaffirmed in the popular press when Popular

Mechanics published its February 1938 article “Billion-Dollar Crop.” The first

reproduction of this article in over 50 years was in the original edition of

this book. The article is reproduced here exactly as it was printed in 1938.

Because of the printing schedule and deadline, Popular Mechanics

prepared this article in spring of 1937 when cannabis hemp for fiber, paper,

dynamite and oil, was still legal to grow and was, in fact, an incredibly

fast-growing industry.

Also reprinted in this chapter is an excerpt from the Mechanical

Engineering article about hemp, published the same month. It originated as a

paper presented a year earlier at the Feb. 26, 1937 Agricultural Processing

Meeting of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers, New Brunswick, New

Jersey.

Harvesting hemp with a grain binder. Hemp grows luxuriously in Texas.

Reports from the USDA during the 1930s, and Congressional

testimony in 1937, showed that cultivated hemp acreage had been doubling in

size in America almost every year from the time it hit its bottom acreage,

1930-when 1,000 acres were planted in the U.S. – to 1937 – when 14,000 acres

were cultivated with plans to continue to double that acreage annually in the

foreseeable future.

As you will see in these articles, the newly mechanized cannabis

hemp industry was in its infancy, but well on its way to making cannabis

America’s largest agricultural crop. And in light of subsequent developments

(e.g. biomass energy technology, building materials, etc.), we now know that

hemp is the world’s most important ecological resource and therefore,

potentially our planet’s single largest industry.

The Popular Mechanics article was the very first time in

American history that the term “billion-dollar” was ever applied to any U.S.

agricultural crop! That is equivalent to $40-$80 billion now.

Experts today conservatively estimate that, once fully restored

in America, hemp industries will generate $500 billion to a trillion dollars

per year, and will save the planet and civilization from fossil fuels and their

derivatives – and from deforestation!

If Harry Anslinger, DuPont, Hearst and their paid-for (know it

or not, then as now) politicians had not outlawed hemp ~ under the pretext of

marijuana (see Chapter 4, “Last Days of Legal Cannabis”) ~ and suppressed hemp

knowledge from our schools, researchers and even scientists, the glowing

predictions in these articles would already have come true by now ~ and more

benefits than anyone could then envision ~ as new technologies and uses

continue to develop.

As one colleague so aptly put it, “These articles were the last

honest word spoken on hemp’s behalf for over 40 years…”

.

NEW BILLION-DOLLAR CROP ~ POPULAR MECHANICS, FEBRUARY 1938

American farmers are promised new cash crop with an annual value of several hundred million dollars, all because a machine has been invented which solves a problem more than 6,000 years old.

It is hemp, a crop that will not compete with other American

products. Instead, it will displace imports of raw material and manufactured

products produced by underpaid coolie and peasant labor and it will provide

thousands of jobs for American workers throughout the land.

The machine which makes this possible is designed for removing

the fiber-bearing cortex from the rest of the stalk, making hemp fiber

available for use without a prohibitive amount of human labor.

Hemp is the standard fiber of the world. It has great tensile

strength and durability. It is used to produce more than 5,000 textile

products, ranging from rope to fine laces, and the woody “hurds” remaining

after the fiber has been removed contains more than seventy-seven per cent

cellulose, and can be used to produce more than 25,000 produces, ranging from

dynamite to Cellophane.

Machines now in service in Texas, Illinois, Minnesota and other

states are producing fiber at a manufacturing cost of half a cent a pound, and

are finding a profitable market for the rest of the stalk. Machine operators

are making a good profit in competition with coolie-produced foreign fiber

while paying farmers fifteen dollars a ton for hemp as it comes from the field.

From the farmers’ point of view, hemp is an easy crop to grow

and will yield from three to six tons per acre on any land that will grow corn,

wheat, or oats. It has a short growing season, so that it can be planted after

other crops are in. It can be grown in any state of the union. The long roots

penetrate and break the soil to leave it in perfect condition for the next

year’s crop. The dense shock of leaves, eight to twelve feet about the ground,

chokes out weeds. Two successive crops are enough to reclaim land that has been

abandoned because of Canadian thistles or quack grass.

Under old methods, hemp was cut and allowed to lie in the fields

for weeks until it “retted” enough so the fibers could be pulled off by hand.

Retting is simply rotting as a result of dew, rain and bacterial action.

.

.

Hemp fiber being delivered from machine ready for baling.

Pile of pulverized herds on the floor are 77% cellulose.

Machines were developed to separate the fibers mechanically after retting was complete, but the cost was high, the loss of fiber great, and the quality of fiber comparatively low. With the new machine, known as a decorticator, hemp is cut with a slightly modified grain binder. It is delivered to the machine where an automatic chain conveyer feeds it to the breaking arms at the rate of two or three tons per hour.

The hurds are broken into fine pieces which drop into the

hopper, from where they are delivered by blower to a baler or to truck or

freight car for loose shipment. The fiber comes from the other end of the

machine, ready for baling.

From this point on almost anything can happen. The raw fiber can

be used to produce strong twine or rope, woven into burlap, used for carpet

warp or linoleum backing or it may be bleached and refined, with resinous

by-products of high commercial value. It can, in fact, be used to replace the

foreign fibers which now flood our markets.

Thousands of tons of hemp hurds are used every year by one large

powder company for the manufacturer of dynamite and TNT. A large paper company,

which has been paying more than a million dollars a year in duties on foreign-made

cigarette papers, now is manufacturing these papers from American hemp grown in

Minnesota.

A new factory in Illinois is producing fine bond papers from

hemp. The natural materials in hemp make it an economical source of pulp for

any grade of paper manufactured, and the high percentage of alpha cellulose

promises an unlimited supply of raw material for the thousands of cellulose

products our chemists have developed.

It is generally believed that all linen is produced from flax.

Actually, the majority comes from hemp ~ authorities estimate that more than

half of our imported linen fabrics are manufactured from hemp fiber. Another

misconception is that burlap is made from hemp. Actually, its source is usually

jute, and practically all of the burlap we use is woven by laborers in India

who receive only four cents a day. Binder twine is usually made from sisal

which comes from Yucatan and East Africa.

All of these products, now imported, can be produced from

home-grown hemp. Fish nets, bow strings, canvas, strong rope, overalls, damask

tablecloths, fine linen garments, towels, bed linen and thousands of other

everyday items can be grown on American farms. Our imports of foreign fabrics

and fibers average about $200,000,000 per year; in raw fibers alone we imported

over $50,000,000 in the first six months of 1937. All of this income can be

made available for Americans.

The paper industry offers even greater possibilities. As an

industry it amounts to over $1,000,000,000 a year, and of that eighty per cent

is imported. But hemp will produce every grade of paper, and government figures

estimate that 10,000 acres devoted to hemp will produce as much paper as 40,000

acres of average pulp land.

One obstacle in the onward march of hemp is the reluctance of

farmers to try new crops. The problem is complicated by the need for proper

equipment a reasonable distance from the farm. The machine cannot be operated

profitably unless there is enough acreage within driving range and farmers

cannot find a profitable market unless there is machinery to handle the crop.

Another obstacle is that the blossom of the female hemp plant contains

marijuana, a narcotic, and it is impossible to grow hemp without producing the

blossom. Federal regulations now being drawn up require registration of hemp

growers, and tentative proposals for preventing narcotic production are rather

stringent.

However, the connection of hemp as a crop and marijuana seems to be exaggerated. The drug is usually produced from wild hemp or locoweed which can be found on vacant lots and along railroad tracks in every state. If federal regulations can be drawn to protect the public without preventing the legitimate culture of hemp, this new crop can add immeasurably to American agriculture and industry.

.

THE MOST PROFITABLE AND DESIRABLE CROP THAT CAN BE GROWN ~ MECHANICAL ENGINEERING, FEBRUARY 26, 1937

“Flax and Hemp: From the Seed to the Loom” was published in the February 1938 issue of Mechanical Engineering magazine. It was originally presented at the Agricultural Processing Meeting of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers in New Brunswick, NY of February 26, 1937 by the Process Industries Division.

.

FLAX AND HEMP: FROM THE SEED TO THE LOOM

BY GEORGE A. LOWER

This country imports practically all of its fibers except cotton. The Whitney gin, combined with improved spinning methods, enabled this country to produce cotton goods so far below the cost of linen that linen manufacture practically ceased in the United States. We cannot produce our fibers at less cost than can other farmers of the world. Aside from the higher cost of labor, we do not get as large production. For instance, Yugoslavia, which has the greatest fiber production per are in Europe, recently had a yield of 883 lbs. Comparable figures for other countries are Argentina, 749 lbs.; Egypt 616 lbs.; and India, 393 lbs.; while the average yield in this country is 383 lbs.

To meet world competition profitably, we must improve our

methods all the way from the field to the loom.

Flax is still pulled up by the roots, retted in a pond, dried in

the sun, broken until the fibers separate from the wood, then spun, and finally

bleached with lye from wood ashes, potash from burned seaweed, or lime.

Improvements in tilling, planting, and harvesting mechanisms have materially

helped the large farmers and, to a certain degree, the smaller ones, but the

processes from the crop to the yarn are crude, wasteful and land injurious.

Hemp, the strongest of the vegetable fibers, gives the greatest

production per acre and requires the least attention. It not only requires no

weeding, but also kills off all the weeds and leaves the soil in splendid

condition for the following crop. This, irrespective of its own monetary value,

makes it a desirable crop to grow.

In climate and cultivation, its requisites are similar to flax

and like flax, should be harvested before it is too ripe. The best time is when

the lower leaves on the stalk wither and the flowers shed their pollen.

Like flax, the fibers run out where leaf stems are on the stalks

and are made up of laminated fibers that are held together by pectose gums.

When chemically treated like flax, hemp yields a beautiful fiber so closely

resembling flax that a high-power microscope is needed to tell the difference –

and only then because in hemp, some of the ends are split. Wetting a few

strands of fiber and holding them suspended will definitely identify the two

because, upon drying, flax will be found to turn to the right or clockwise, and

hemp to the left or counterclockwise.

Before [World War I], Russia produced 400,000 tons of hemp, all

of which is still hand-broken and hand-scutched. They now produce half that

quantity and use most of it themselves, as also does Italy from whom we had

large importations.

.

.

In this country, hemp, when planted one bu. per acre, yields about three tons of dry straw per acre. From 15 to 20 percent of this is fiber, and 80 to 85 percent is woody material. The rapidly growing market for cellulose and wood flower for plastics gives good reason to believe that this hitherto wasted material may prove sufficiently profitable to pay for the crop, leaving the cost of the fiber sufficiently low to compete with 500,000 tons of hard fiber now imported annually.

Hemp being from two to three times as strong as any of the hard

fibers, much less weight is required to give the same yardage. For instance,

sisal binder twine of 40-lb. tensile strength runs 450 ft. to the lb. A better twine

made of hemp would run 1280 ft. to the lb. Hemp is not subject to as many kinds

of deterioration as are the tropical fibers, and none of them lasts as long in

either fresh or salt water.

While the theory in the past has been that straw should be cut

when the pollen starts to fly, some of the best fiber handled by Minnesota hemp

people was heavy with seed. This point should be proved as soon as possible by

planting a few acres and then harvesting the first quarter when the pollen is

flying, the second and third a week or 10 days apart, and the last when the

seed is fully matured. These four lots should be kept separate and scutched and

processed separately to detect any difference in the quality and quantity of

the fiber and seed.

Several types of machines are available in this country for

harvesting hemp. One of these was brought out several years ago by the

International Harvester Company. Recently, growers of hemp in the Middle West

have rebuilt regular grain binders for this work. This rebuilding is not

particularly expensive and the machines are reported to give satisfactory

service.

Degumming of hemp is analogous to the treatment given flax. The

shards probably offer slightly more resistance to digestion. On the other hand,

they break down readily upon completion of the digestion process. And excellent

fiber can, therefore, be obtained from hemp also. Hemp, when treated by a known

chemical process, can be spun on cotton, wool, and worsted machinery, and has

as much absorbency and wearing quality as linen.

Several types of machines for scutching the hemp stalks are also

on the market. Scutch mills formerly operating in Illinois and Wisconsin used

the system that consisted of a set of eight pairs of fluted rollers, through

which the dried straw was passed to break up the woody portion. From there, the

fiber with adhering shards ~ or hurds, as they are called ~ was transferred by

an operator to an endless chain conveyer. This carries the fiber past two

revolving single drums in tandem, all having beating blades on their periphery,

which beat off most of the hurds as well as the fibers that do not run the full

length of the stalks.

The proportion of line fiber to tow is 50% each. Tow or short

tangled fibers then go to a vibrating cleaner that shakes out some of the

hurds. In Minnesota and Illinois, another type has been tried out. This machine

consists of a feeding table upon which the stalks are placed horizontally.

Conveyor chains carry the stalks along until they are grasped by a clamping

chain that grips them and carries them through half of the machine.

.

.

A pair of intermeshing lawnmower-type beaters are placed at a 45-degree angle to the feeding chain and break the hemp stalks over the sharp edge of a steel plate, the object being to break the woody portion of the straw and whip the hurds from the fiber. On the other side and slightly beyond the first set of lawnmower beaters is another set, which is placed 90-degrees from the first pair and whips out the hurds.

The first clamping chain transfers the stalks to another to

scutch the fiber that was under the clamp at the beginning. Unfortunately, this

type of scutcher makes even more tow than the so-called Wisconsin type. This

tow is difficult to re-clean because the hurds are broken into long slivers

that tenaciously adhere to the fiber.

Another type passes the stalks through a series of graduated

fluted rollers. This breaks up the woody portion into hurds about 3/4 inch

long, and the fiber then passes on through a series of reciprocating slotted

plates working between stationary slotted plates.

Adhering hurds are removed from the fiber which continues on a

conveyer to the baling press. Because no beating of the fiber against the grain

occurs, this type of scutcher make only line fiber. This is then processed by

the same methods as those for flax.

Paint and lacquer manufacturers are interested in hempseed oil

which is a good drying agent. When markets have been developed for the products

now being wasted, seed and hurds, hemp will prove, both for the farmer and the

public, the most profitable and desirable crop that can be grown, and one that

can make American mills independent of importations.

Recent floods and dust storms have given warnings against the