Source: The Ugly Truth

July

24, 2013

Over the past

three years, my wife Pennie and I have been working on a documentary film about

the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. During our second production trip to the

region, one of the many remarkable people we encountered was Uri Davis. He is

one of a handful of Israelis who has built a life for himself among the

Palestinians of the West Bank. This made him a very interesting subject for our

film, which examines the practical and moral failings of the two-state

solution.

During our

interview with Davis, one of the questions we asked was whether he had

encountered any anti-Semitism in the West Bank. The question was motivated by a

desire on our part to address a narrative ~ prevalent among American and

Israeli Jews ~ which claims that anti-Semitism is an obvious feature of

Palestinian culture.

As these two groups are an important part of our target audience, we felt that

it was our responsibility to address this perception. Who better to ask about

the veracity of this narrative than a Jew living among Palestinians?

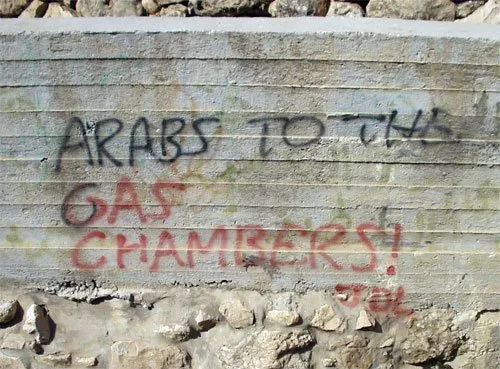

Davis answered by saying that although Palestinian anti-Semitism does exist, it is a marginal phenomenon, while anti-Arab sentiment among Israelis is a mainstream phenomenon.

Shortly after the interview, it occurred to us

that we could either substantiate or disprove Davis’s provocative statement

with our cameras.

We began our

survey in February 2011 and completed it in early March. On the Israeli side,

we interviewed a total of 250 Jewish Israelis in Haifa, Tel Aviv, Herzliya,

Jerusalem and Beersheba. For this part of the survey I conducted the interviews

myself from behind the camera in Hebrew.

On the

Palestinian side, we interviewed a total of 250 Palestinians in Jenin, Nablus,

Ramallah, Bethlehem and Hebron. (Despite multiple attempts, we were unable to

procure permission to enter the Gaza Strip.) Here, we collaborated with local

journalist Mohammad Jaradat who, using my questions, conducted the interviews

in Arabic.

The questions we

asked pertained to a number of sensitive political topics and the idea was to

get people to talk long enough to detect if there was any racism at play in

their answers. In sociological terms, we were engaged in qualitative analysis,

but unlike typical qualitative interviews, we spent minutes, not hours with our

subjects.

Our survey is not

exhaustive and our method was very simple. We went to public places and asked

people to talk to us on camera. In designing the questions, I set out to

distinguish actual racism from conflict-based animosity. That is, to allow for

the possibility that Israelis might exhibit animosity towards Palestinians

without being racist and to allow the same on the Palestinian side in reverse.

The very first

question we asked of Jewish Israelis was the extremely broad “What do you think

about Arabs?” It is only reasonable to expect that people who harbour anti-Arab

sentiment would mask their feelings when answering such a direct question on

camera. Most people responded to this question with some variation of “They are

people,” although we were surprised that a sizable minority used the

opportunity to launch into anti-Arab diatribes.

One of the most

disturbing trends that we noticed was the strong correlation between age and

anti-Arab sentiment. The majority of Israeli teenagers that we spoke to

expressed unabashed and open racism towards Arabs. Statements like “I hate

them,” or “They should all be killed” were common in this age group.

When looking over

the data, we divided the respondents into three groups: those who were neutral

about Arabs; those who were positive about them; and those who expressed

negative attitudes. Amongst the responses, 60 percent were neutral, 25 percent

negative and 15 percent positive.

.

.

Rights

misunderstood

Interestingly,

some of the same people who answered the first question by saying that Arabs

are people, went on to say that they wouldn’t be willing to live next door to

them. Internal inconsistencies of this nature cropped up in many of the

interviews and it is for this reason that we reserved our overall judgment on

the prevalence of anti-Arab sentiment until all of the answers were tabulated.

Our results show that 71 percent were willing to live next door to Arab neighbours,

while 24 percent were unwilling. Five percent failed to answer this question

with either a “yes” or a “no.”

It should be

noted that the Israel Democracy Institute received dramatically different numbers

in response to the above question. In its 2010 survey, it found that 46 percent

of Jewish Israelis were unwilling to live next door to an Arab. The implication

of this discrepancy is that our survey sample was much less anti-Arab than the

population at large.

When it came to

equal rights, a clear majority of our respondents answered that they felt it

was important for Arab citizens of the state of Israel to enjoy equal rights.

Upon review of the data, one of the significant trends that emerged in these

answers was the recurrent use of the phrase “rights and responsibilities.”

Many people openly resented the fact that most Arab citizens of the state don’t perform military service and argued that Arabs should only have equal rights if they are held to the same responsibilities as Jews.

This response

demonstrates a profound misunderstanding of the very concept of rights, but it

was prevalent enough that we felt it justified its own category. We called this

category “conditional.” Of these responses, 64 percent were in favour of equal

rights, 16 percent were opposed and 20 percent were in favour of conditional

rights.

Once again, we

saw a clear discrepancy from the Israel Democracy Institute numbers, which

showed that 46 percent of Israelis were opposed to full and equal rights for

Arab citizens of the state.

.

.

Democracy

for Jews only?

Israel defines

itself as a “Jewish democracy” but we were interested in discovering which part

of that definition is more important to Jewish Israelis. We went about doing

this by asking:

“What’s more important: that Israel be a Jewish state or a democratic state?”

What we

discovered was that a clear majority of the people we spoke to felt that the

Jewish character of the state was at least equally if not more important than

the democratic character. There was, however, an impressive minority who were

clear about the fact that it was more important to them that Israel be a

democratic state. This last category represents, by a slim margin, the single

largest group of our respondents: 37 percent felt that a democratic character

was more important, 36 percent felt that a Jewish character was more important

and 27 percent felt that both were equally important.

On the subject of

the settlers,

we asked a more leading question:

“What do you think about the settlers? Are they an impediment to peace?”

We broke the

responses down into three groups: those who were neutral about the settlers;

those who were positive about them; and those who expressed negativity. In this

instance, answering “yes” was taken as evidence of negative feelings towards

the settlers, answering “no” without qualification was taken as a neutral

stance and answering “no” followed by something like “they are the heroes of

the Jewish people” ~ a phrase that we heard a number of times ~ was taken as

evidence of positive feelings. What we discovered was that more than 70 percent

of the people we spoke to were either neutral or positive towards the settlers.

Of the responses, 45 percent were neutral, 28 percent were positive and 27

percent were negative about the settlers.

ED Noor: Remember that these are the folks who have made a shrine of the grave of mass murderer Baruch Goldstein and who award their bloodiest soldiers for services rendered. So of course there would be admiration for these settlers in this rogue nation.

Many of the

people we spoke to exhibited a deep suspicion and mistrust of the Palestinian

people. When asked whether it was possible to make peace with the Palestinians,

less than half of our respondents answered “yes.” This is a sobering statistic

for anyone invested in the peace process.

It would seem

that most of the people we spoke to have given up on the prospect of peace.

Even among the Israelis who believed that peace is possible, a recurrent theme

was “not in this generation.”

Another important

trend in this part of the survey was blaming the Palestinian leadership for the

lack of progress in the peace process. Many of the people who answered “yes”

stated that peace was possible with the Palestinian people but not with their

leaders. Of the responses, 48 percent believed that peace with the Palestinians

is possible, while 40 percent felt that peace is not possible. Thirteen percent

failed to answer this question with either a “yes” or a “no.”

Little

knowledge of one-state solution

Given the subject

of our film, we were very interested in exploring people’s preferences for

potential solutions to the conflict. What we noticed almost immediately was that

it was very important to clarify to our respondents exactly what we meant by

one state or two states. For the purposes of our survey, we defined the

one-state solution as a secular democracy with equal rights on all of historic

Palestine, while we defined the two-state solution as two states more or less

along the lines of the 1967 boundaries, with East Jerusalem as the capital of

the Palestinian state. It was important that we were able to explain exactly

what we meant, because many Israelis answered one way but meant something

entirely different.

For example, when

asked whether they preferred the one-state solution or the two-state solution,

many respondents answered that they preferred the two-state solution. But when

we followed up and asked what territorial concessions they would be willing to

make, these same people said that they wouldn’t agree to any concessions.

Furthermore,

almost no one that we spoke to was familiar with the concept of the one-state

solution. Many people even took this to mean one state for Jews only, until we

clarified our meaning.

When we reviewed

the data from this section of the survey, we decided to break down the

responses into seven different categories: one state; one state (i.e. a state

for Jews only); two states; two states (i.e. without territorial concessions);

either one or two states; neither one nor two states; and other.

What is really

fascinating about our results is that over two thirds of the people we spoke to

were actively opposed to the classic two-state solution on the 1967 borders.

Furthermore, there were almost as many true one-state solution supporters as

there were classic two-state supporters.

Amongst those we

surveyed, 27 percent were true two-state supporters, 23 percent were true one

state supporters, 22 percent supported neither, 16 percent were in favour of

two states without territorial concessions, 6 percent were okay with either one

or two states, 4 percent were in favour of one state for Jews only, and 2

percent didn’t fit into any of these categories.

.

.

Racism

highest in Jerusalem

In trying to

answer the question of whether anti-Arab sentiment is a mainstream phenomenon

among Israelis, we looked at all of the answers and divided the data into three

categories: not anti-Arab; mildly anti-Arab; and strongly anti-Arab.

Once again, we

allowed for the possibility that a person might exhibit animosity towards

Palestinians without being anti-Arab and we did not put people into one of the

anti-Arab columns simply because he or she expressed right-wing political

views. So, for example, if the only evidence in an interview of anti-Arab

sentiment was that the respondent said that equal rights for Arabs are

conditional upon equal responsibilities, we did not put them in an anti-Arab

column. However, if a respondent stated that they wouldn’t live next door to an

Arab, this was sufficient to push him or her into the mildly anti-Arab column.

To qualify for the strongly anti-Arab category, a respondent needed to exhibit

anti-Arab sentiment in two or more answers.

Our results

showed that 46 percent of our respondents were either mildly or strongly

anti-Arab. When we broke these numbers down according to city, there were

obvious regional differences. Jerusalem was by far the most anti-Arab of the

five cities we visited, with 58 percent exhibiting some level of anti-Arab

sentiment, while Haifa was the least with 32 percent. Interestingly, after

Jerusalem, Tel Aviv was the city with the most anti-Arab sentiment (49

percent).

The data we gathered substantiates the idea that anti-Arab sentiment is a mainstream phenomenon in Israel.

Almost half of

all the Jewish Israelis we spoke to exhibited some level of anti-Arab

sentiment. The single most disturbing trend that emerged was the correlation

between youth and strong anti-Arab sentiment.

We also learned

that support for the classic two-state solution along the 1967 lines was very

low among the people we spoke to. This data point

was reinforced by the strong support that we saw for the settlers.

Given our leading

question, the fact that less than a third of respondents were willing to

characterize the settlers as an impediment to peace, is further evidence that

the two-state solution, as it is currently being proposed by the international

community, is decidedly unpopular in Israel.

Despite the lack

of knowledge about the one-state solution idea, some respondents appeared

willing to consider it. Once this solution was explained to them, 22 percent

preferred it and around 6 percent did not object to it. Finally, when we asked

Jewish Israelis to choose between the Jewish character of the state and the

democratic character, 36 percent opted for the latter. All of these results

must be taken with a grain of salt.

We can report

anecdotally that many of the people who refused to be interviewed told us that

they wouldn’t participate, because they felt that we were part of the “leftist

media.” For these reasons, we feel that it is likely, if anything, that our

data underestimates the actual amount of anti-Arab sentiment in Israel.

No comments:

Post a Comment

If your comment is not posted, it was deemed offensive.