What would happen if bombs landed on your street? This is how it is when the Israelis do just such a thing in Gaza. Warning: Contains footage of holocaust victims that some viewers may find distressing.

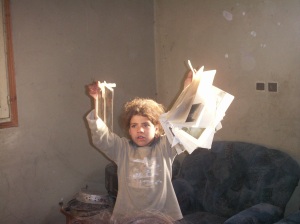

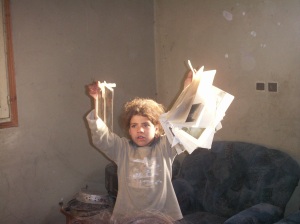

10-year-old Palestinian Mona Samouni stoically describes how she became one of the very few survivors of the extended Samouni family, after the Israeli army's slaughter in the densely populated Zeitoun district in Gaza. She saw 48 members slaughtered including her mother and siblings. Warning: Contains footage of holocaust victims that some viewers may find distressing. January, 2009.

Amid dust and death,

a family's story speaks for the terror of war

48 members of the Samouni family were killed in one day when Israel's battle with Hamas suddenly centred on their homes

Helmi Samouni knelt yesterday on the floor of the bedroom he once shared with his wife and their five-month old son, scraping his fingers through a thick layer of ash and broken glass looking for mementoes of their life together. “I found a ring. I might find more,” he said.

His wife Maha and their child Muhammad were killed in the second week of Israel’s 22-day war in Gaza when they were shelled by Israeli forces as they took shelter nearby along with dozens of relatives. In total 48 people from one family are now known to have died that Monday morning, 5 January, in Zeitoun, on the southern outskirts of Gaza City.

Of all the horrors visited on the civilians of Gaza in this war the fate of the Samounis, a family of farmers who lived close together in simple breeze-block homes, was perhaps the gravest.

Around a dozen homes in this small area were destroyed, no more than piles of rubble in the sand yesterday. Helmi Samouni’s two-storey house was one of the few left standing, despite the gaping hole from a large tank shell that pierced his blackened bedroom wall. During the invasion it had been taken over by Israeli soldiers, who wrecked the furniture and set up sand-bagged shooting positions throughout.

They left behind their own unique detritus: bullet casings, roasted peanuts in tins with Hebrew script, a plastic bag containing a “High Quality Body Warmer”, dozens of olive-green waste disposal bags, some empty, some stinking full ~ the troops’ portable toilets.

But most disturbing of all was the graffiti they daubed on the walls of the ground floor. Some was in Hebrew, but much was naively written in English: “Arabs need 2 die”, “Die you all”, “Make war not peace”, “1 is down, 999,999 to go”, and scrawled on an image of a gravestone the words: “Arabs 1948-2009″.

There were several sketches of the Star of David flag. “Gaza here we are,” it said in English next to one.

Helmi’s brother Salah, 30, had an apartment in the same house. He too was pulling out what he could, including an Israeli work permit once issued to his father. “They gave him a permit and then they came from Israel and they killed him,” said Salah. In the attack he lost both his parents, Talal and Rahma, and his two-year-old daughter Aza.

During the war, Israel banned journalists from entering Gaza. But the accounts of Salah and his neighbours outside the rubble of their homes yesterday corroborate the accounts from witnesses given in the days after the attack, accounts which led the UN to describe the killings at Zeitoun as one of the gravest episodes of the war and the Red Cross to call it, in a rare public rebuke, “a shocking incident”.

More than a dozen bodies were pulled from the rubble on Sunday, and one more yesterday, bringing the Samouni death toll to 48, according to Dr Mouawia Hassanein, head of Gaza’s Emergency Medical Services. With more bodies being recovered each day, the death toll from Israel’s three-week war now stands at 1,360. On the Israeli side, 13 were killed.

On the second Saturday of the war, after a week of Israeli air strikes, there came a wave of heavy artillery shelling which preceded the ground invasion of Gaza. That night, Salah Samouni took shelter on the ground floor with 16 others from his family. By the next morning, Sunday 4 January, more neighbours had come looking for shelter and the number now there was approaching 50.

“They fired a shell into the upstairs floor and it started a fire,” said Salah. “We called the ambulance and the fire service, but no one was able to reach us.” Soon a group of Israeli soldiers approached. “They came and banged on the door and told everyone to leave the house,” he said. They walked a few metres down the dirt road and entered the large, single-storey home of Wa’el Samouni.

There they stayed for the rest of the day, now a group of around 100 men, women and children, with no food and little water. Though there may have been Palestinian fighters operating in the open fields around the houses, all the witnesses are adamant that those gathered in Wa’el Samouni’s house were all civilians and all from the same extended family.

On the Monday morning, four of the men ~ Salah among them ~ decided to go out to bring back firewood for cooking. “They fired a shell straight at us,” Salah said. Two of the four were killed instantly, the other two were injured. Salah was hit by shrapnel on his forehead, his back and his legs. Moments later, he said, two more shells struck the house, killing dozens of them.

Salah and a group of around 70 fled the house, shouting to the soldiers that there were women and children with them. They ran to the main road and on for a kilometre until ambulances could reach them. Others stayed behind.

Wa’el Samouni’s father, Faris, 59, lived next door to the house where the crowd had taken shelter. He had a single-storey house with only a corrugated iron roof and so his family had moved next door to shelter, but he had stayed behind. He was unable to leave his building for fear of being shot, but on the Tuesday the survivors called to him to bring water. He ran quickly the short distance and joined them.

“Dead bodies were lying on the ground. Some people were injured, they were just trying to help each other,” he said. There among the dead Faris found his wife Rizka, 50; his daughter-in-law Anan; and his granddaughter Huda, 16.

Only on the afternoon of the following day, the Wednesday, were the survivors rescued when the Red Cross arrived to carry them out to hospital.

The Israeli military has said it is investigating what happened at Zeitoun. It has repeatedly denied that its troops ordered the residents to gather in one house and said its troops do not intentionally target civilians.

Others in the family saw a different but equally grim fate. Faraj Samouni, 22, lived with his family next door to Helmi and Salah. Again on the Saturday evening the family had sought shelter from the heavy shelling, a group of 18 of them gathering in one room for the night. On the Sunday morning the Israeli soldiers approached. “They shouted for the owner of the house to come out. My father opened the door and went out and they shot him right there,” said Faraj.

With the body of his father Atiya, 45, slumped on the ground outside, the soldiers fired more shots into the room, he said, this time killing Faraj’s younger half-brother Ahmad, who was four years old, and the child’s mother.

Yesterday there was blood on the wall of the small room where the child had been sitting.

Then the troops ordered them to lie on the floor. But when a fire started burning in the room next door, sending in acrid smoke, they began shouting to be allowed out. “We were shouting ‘babies, children’,” Faraj said.

Eventually the soldiers let them out and they ran along the street, passing the others who had gathered in Wa’el Samouni’s house and making their way out on to the main road and to safety.

When Faraj returned, he found his home completely destroyed, a pile of twisted iron bars and concrete. On a small outdoor grill were the charred remains of the eight aubergines that the family had been cooking that Sunday morning for their breakfast.

Only on Sunday was he able to bury his father’s body and even then there was a final injustice: Gaza’s graves are now so crowded and concrete so scarce because of Israel’s long blockade that he had to break open an older family grave and put his father in with the other corpse.

“How can we have peace when they are killing civilians, even children?” said Faraj. “I support the ceasefire now. We have no power. If there wasn’t a ceasefire we couldn’t even bury our dead.”

Some Gazans speak privately of their anger at Hamas, blaming the Islamist movement that rules the small territory for dragging them into this conflict. But by far the larger majority are speaking now of their bitter anger at Israel and their deep resentment at the apathy of the Arab world and the rest of the international community, which failed to halt the destruction and the killing.

“We blame everyone,” said Ibrahim Samouni, 45, who lost his wife and four of his sons in the killings at Zeitoun. “We need everyone to look at us and see what has happened here. We are not resistance fighters. We are ordinary people.”

His wife Maha and their child Muhammad were killed in the second week of Israel’s 22-day war in Gaza when they were shelled by Israeli forces as they took shelter nearby along with dozens of relatives. In total 48 people from one family are now known to have died that Monday morning, 5 January, in Zeitoun, on the southern outskirts of Gaza City.

Of all the horrors visited on the civilians of Gaza in this war the fate of the Samounis, a family of farmers who lived close together in simple breeze-block homes, was perhaps the gravest.

Around a dozen homes in this small area were destroyed, no more than piles of rubble in the sand yesterday. Helmi Samouni’s two-storey house was one of the few left standing, despite the gaping hole from a large tank shell that pierced his blackened bedroom wall. During the invasion it had been taken over by Israeli soldiers, who wrecked the furniture and set up sand-bagged shooting positions throughout.

They left behind their own unique detritus: bullet casings, roasted peanuts in tins with Hebrew script, a plastic bag containing a “High Quality Body Warmer”, dozens of olive-green waste disposal bags, some empty, some stinking full ~ the troops’ portable toilets.

But most disturbing of all was the graffiti they daubed on the walls of the ground floor. Some was in Hebrew, but much was naively written in English: “Arabs need 2 die”, “Die you all”, “Make war not peace”, “1 is down, 999,999 to go”, and scrawled on an image of a gravestone the words: “Arabs 1948-2009″.

There were several sketches of the Star of David flag. “Gaza here we are,” it said in English next to one.

Helmi’s brother Salah, 30, had an apartment in the same house. He too was pulling out what he could, including an Israeli work permit once issued to his father. “They gave him a permit and then they came from Israel and they killed him,” said Salah. In the attack he lost both his parents, Talal and Rahma, and his two-year-old daughter Aza.

During the war, Israel banned journalists from entering Gaza. But the accounts of Salah and his neighbours outside the rubble of their homes yesterday corroborate the accounts from witnesses given in the days after the attack, accounts which led the UN to describe the killings at Zeitoun as one of the gravest episodes of the war and the Red Cross to call it, in a rare public rebuke, “a shocking incident”.

More than a dozen bodies were pulled from the rubble on Sunday, and one more yesterday, bringing the Samouni death toll to 48, according to Dr Mouawia Hassanein, head of Gaza’s Emergency Medical Services. With more bodies being recovered each day, the death toll from Israel’s three-week war now stands at 1,360. On the Israeli side, 13 were killed.

On the second Saturday of the war, after a week of Israeli air strikes, there came a wave of heavy artillery shelling which preceded the ground invasion of Gaza. That night, Salah Samouni took shelter on the ground floor with 16 others from his family. By the next morning, Sunday 4 January, more neighbours had come looking for shelter and the number now there was approaching 50.

“They fired a shell into the upstairs floor and it started a fire,” said Salah. “We called the ambulance and the fire service, but no one was able to reach us.” Soon a group of Israeli soldiers approached. “They came and banged on the door and told everyone to leave the house,” he said. They walked a few metres down the dirt road and entered the large, single-storey home of Wa’el Samouni.

There they stayed for the rest of the day, now a group of around 100 men, women and children, with no food and little water. Though there may have been Palestinian fighters operating in the open fields around the houses, all the witnesses are adamant that those gathered in Wa’el Samouni’s house were all civilians and all from the same extended family.

On the Monday morning, four of the men ~ Salah among them ~ decided to go out to bring back firewood for cooking. “They fired a shell straight at us,” Salah said. Two of the four were killed instantly, the other two were injured. Salah was hit by shrapnel on his forehead, his back and his legs. Moments later, he said, two more shells struck the house, killing dozens of them.

Salah and a group of around 70 fled the house, shouting to the soldiers that there were women and children with them. They ran to the main road and on for a kilometre until ambulances could reach them. Others stayed behind.

Wa’el Samouni’s father, Faris, 59, lived next door to the house where the crowd had taken shelter. He had a single-storey house with only a corrugated iron roof and so his family had moved next door to shelter, but he had stayed behind. He was unable to leave his building for fear of being shot, but on the Tuesday the survivors called to him to bring water. He ran quickly the short distance and joined them.

“Dead bodies were lying on the ground. Some people were injured, they were just trying to help each other,” he said. There among the dead Faris found his wife Rizka, 50; his daughter-in-law Anan; and his granddaughter Huda, 16.

Only on the afternoon of the following day, the Wednesday, were the survivors rescued when the Red Cross arrived to carry them out to hospital.

The Israeli military has said it is investigating what happened at Zeitoun. It has repeatedly denied that its troops ordered the residents to gather in one house and said its troops do not intentionally target civilians.

Others in the family saw a different but equally grim fate. Faraj Samouni, 22, lived with his family next door to Helmi and Salah. Again on the Saturday evening the family had sought shelter from the heavy shelling, a group of 18 of them gathering in one room for the night. On the Sunday morning the Israeli soldiers approached. “They shouted for the owner of the house to come out. My father opened the door and went out and they shot him right there,” said Faraj.

With the body of his father Atiya, 45, slumped on the ground outside, the soldiers fired more shots into the room, he said, this time killing Faraj’s younger half-brother Ahmad, who was four years old, and the child’s mother.

Yesterday there was blood on the wall of the small room where the child had been sitting.

Then the troops ordered them to lie on the floor. But when a fire started burning in the room next door, sending in acrid smoke, they began shouting to be allowed out. “We were shouting ‘babies, children’,” Faraj said.

Eventually the soldiers let them out and they ran along the street, passing the others who had gathered in Wa’el Samouni’s house and making their way out on to the main road and to safety.

When Faraj returned, he found his home completely destroyed, a pile of twisted iron bars and concrete. On a small outdoor grill were the charred remains of the eight aubergines that the family had been cooking that Sunday morning for their breakfast.

Only on Sunday was he able to bury his father’s body and even then there was a final injustice: Gaza’s graves are now so crowded and concrete so scarce because of Israel’s long blockade that he had to break open an older family grave and put his father in with the other corpse.

“How can we have peace when they are killing civilians, even children?” said Faraj. “I support the ceasefire now. We have no power. If there wasn’t a ceasefire we couldn’t even bury our dead.”

Some Gazans speak privately of their anger at Hamas, blaming the Islamist movement that rules the small territory for dragging them into this conflict. But by far the larger majority are speaking now of their bitter anger at Israel and their deep resentment at the apathy of the Arab world and the rest of the international community, which failed to halt the destruction and the killing.

“We blame everyone,” said Ibrahim Samouni, 45, who lost his wife and four of his sons in the killings at Zeitoun. “We need everyone to look at us and see what has happened here. We are not resistance fighters. We are ordinary people.”

“We have no bathroom, how can we wash ourselves? How can we go to school looking like this?”, implored 13 year-old Shaima al Samouni. It’s a pertinent question, given that schools reopened two days ago for the first time since the Israeli attacks on Gaza started.

With 29 family members killed during the attacks on the Zeitoon neighbourhood in Gaza city, however, it seems a strange concern. But life marches on, and the other children have gone back to school. Tugging at the clothes they were wearing, the children explain that, now, three weeks after their homes were destroyed, what they’re wearing is all they have. And, it seems, they’re not going to school wearing that.

They take us across the dirt, to a half-bombed house. On the way, we walk over the foundations of what used to be the house of Majid al Samouni and his family. The children stop to show us a drum of olives (zeitoon) that was destroyed.

We pass by the carcass of a large sheep. Shot by the Israeli army. They show us their two pretty donkeys. “Donkeys quais”, I say in broken Arabic, relieved that they’re not taking us to more animal corpses.

There used to be nine donkeys, they explain. But the Israeli soldiers shot seven of them. Then my colleague points out the gaping hole in the shoulder of the brown donkey ~ also shot by the Israeli army. Donkey mish quais.

We pass by the carcass of a large sheep. Shot by the Israeli army. They show us their two pretty donkeys. “Donkeys quais”, I say in broken Arabic, relieved that they’re not taking us to more animal corpses.

There used to be nine donkeys, they explain. But the Israeli soldiers shot seven of them. Then my colleague points out the gaping hole in the shoulder of the brown donkey ~ also shot by the Israeli army. Donkey mish quais.

One of the young girls, who is nine years old, is desperate for me to understand the extent to which their lives were destroyed. Not in terms of life lost, but livelihood. “Bas al shugul ~ al ard. Bas” (The land is the only work we have), and the land is totally destroyed.

The children catalogue the types of fruit trees they had ~ lemon, guava, orange, mandarin, and the ubiquitous olive.

They don’t talk about the battery-chicken shed that is crushed, chickens still in cages. When i finally ask just how many chickens there were, I find it difficult to believe the answer ~ two thousand chickens.

The children catalogue the types of fruit trees they had ~ lemon, guava, orange, mandarin, and the ubiquitous olive.

Her older cousin goes to great lengths to tell me repeatedly, at every opportunity, that they were just farmers, not Hamas. I know, I reply.

Inside the half-destroyed house, there is a clamour to show all of the atrocities crowded into one small space. Some of the children explain that their mother had given birth during the bombing, how they had to burn a knife over a candle to cut the umbilical cord.

And about how their two-year-old sister was wounded on her face ~ lacerations from her eye across and down her cheek. Others point to where shells entered the house, some still stuck in the walls. They tell us how the soldiers had occupied the house, after the family had evacuated it. How they came back to find everything on the ground, including the Qu’ran.

Then, worse, how one Qu’ran had been defecated on.

Haram, was all I could say. I took photos somewhat helplessly, of everything they showed me. I’m well-practiced at documenting damage Israeli soldiers have done to Palestinian homes. And the families always seem to feel better if you take photos of everything. But the ridiculousness of what I was doing ~ taking photos of small holes in walls when half of the house was missing ~ hit, and I put the camera down.

And about how their two-year-old sister was wounded on her face ~ lacerations from her eye across and down her cheek. Others point to where shells entered the house, some still stuck in the walls. They tell us how the soldiers had occupied the house, after the family had evacuated it. How they came back to find everything on the ground, including the Qu’ran.

Then, worse, how one Qu’ran had been defecated on.

Haram, was all I could say. I took photos somewhat helplessly, of everything they showed me. I’m well-practiced at documenting damage Israeli soldiers have done to Palestinian homes. And the families always seem to feel better if you take photos of everything. But the ridiculousness of what I was doing ~ taking photos of small holes in walls when half of the house was missing ~ hit, and I put the camera down.

A couple of the children ~ the ones who had been telling me that they were all farmers, and just farmers ~ led me around the corner to a house they said belonged to Arafat al Samouni. The house was leveled, just a small tarp erected in the middle of the debris.

“Sleep here” one of the children informed. 10 people killed in that house. Just one left, seemingly. Haram.

“Sleep here” one of the children informed. 10 people killed in that house. Just one left, seemingly. Haram.

I wanted to ask the children about their parents. I know at least some of them have surviving parents, saw them with their mother. Heard them talk about her. But I’m too scared to ask. I don’t want to hear a small child have to tell me that its parent or parents are dead. There’s so much i can’t bring myself to ask.

I’ve taken a lot of reports in Palestine. I know how it goes. What you need to ask. What information is vital. I know it so well I don’t even need to think about it. I can ask with sympathy about how Israeli soldiers invaded a family home; beat people; abducted their children.

But this is something else entirely. Here and now, such questions seem vile. I just want to hang out with the children. Let them show me what they want to show me. Listen to them talk.

I’ve taken a lot of reports in Palestine. I know how it goes. What you need to ask. What information is vital. I know it so well I don’t even need to think about it. I can ask with sympathy about how Israeli soldiers invaded a family home; beat people; abducted their children.

But this is something else entirely. Here and now, such questions seem vile. I just want to hang out with the children. Let them show me what they want to show me. Listen to them talk.

While we’re hanging out with these kids, our friends encounter one of their cousins who watched both of her parents die when Israeli soldiers bombed a house that they had told everyone from neighbouring houses to shelter in.

SECOND VIDEO ABOVE, MONA SAMOUNI SPEAKS

Later, watching the video they took, we’re all shocked by the confident way Mona talks about the night when so many from her extended family were killed. About how she watched her parents die, before the rest of the family ran from the house, in all directions, whilst they were being fired upon by the soldiers.

How composed she is as she recalls how they ran to her school, which she had previously believed was a long way from here house. How she couldn’t believe she had walked all that way. How it didn’t seem like a long distance. And about how here grandparents told her that it was because they were scared and running that she didn’t notice the distance.

SECOND VIDEO ABOVE, MONA SAMOUNI SPEAKS

Later, watching the video they took, we’re all shocked by the confident way Mona talks about the night when so many from her extended family were killed. About how she watched her parents die, before the rest of the family ran from the house, in all directions, whilst they were being fired upon by the soldiers.

How composed she is as she recalls how they ran to her school, which she had previously believed was a long way from here house. How she couldn’t believe she had walked all that way. How it didn’t seem like a long distance. And about how here grandparents told her that it was because they were scared and running that she didn’t notice the distance.

We’re not the only foreigners visiting this area ~ the al Samouni family have become famous for the tragedy they’ve endured. Teams of international journalists traipse around the dirt mounds and debris, making it seem like a macabre tourist attraction.

“This is why the children don’t seem sad”, a local friend suggests later, while we watch Mona’s video. “When all the journalists leave, then they will feel sad”.

“This is why the children don’t seem sad”, a local friend suggests later, while we watch Mona’s video. “When all the journalists leave, then they will feel sad”.

Driving back down the road towards Gaza city, we pass building after building bearing signs of shelling and bombing. Metre-wide holes punched through walls ~ some covered in plastic; a few already bricked in; most still open wounds in the masonry. It looks to me as though tanks drove down the street we now drive on, pausing to shell every apartment block and house they passed. As though for fun.

It’s an idea I can’t get out of my mind. The possibility that a large proportion of what the al Samounis and other families in Gaza have endured over the past month was done for kicks haunts me.

It’s an idea I can’t get out of my mind. The possibility that a large proportion of what the al Samounis and other families in Gaza have endured over the past month was done for kicks haunts me.

No comments:

Post a Comment

If your comment is not posted, it was deemed offensive.