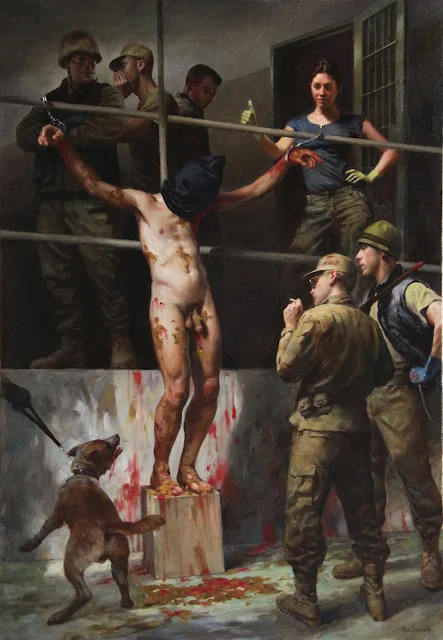

“Torture Abu Ghraib,” 46” x

32” oil on canvas, 2009, is reminiscent of the crucifixion of Christ in an

effort to express Ginsburg’s outrage at the hypocrisy of the religious leaders

who supported the war and torture.

In homage to Caravaggio’s images of Christ on the cross,

Ginsburg has masterfully, and vividly, illustrated an infamous torture scene

from the Abu Ghraib prison, again symbolically pointing out the hypocrisy of

our leaders who claim to be religious followers of Jesus Christ.

TRUE TO WHAT’S

REAL:

PAINTER MAX

GINSBURG RECORDS THE SOCIAL CONDITION

By

Joanne Zuhl

Reposted by Noor June 9, 2012

“Foreclosure,” by Max

Ginsburg, 40” x 65” .oil, 2011, depicts the anguish and frustration of people in

foreclosure. Of this painting, Ginsburg, shown below, says, “It is

unconscionable that people are being evicted from their homes, especially when

banks and corporations are being bailed out. This injustice is not supposed to

happen in America.”

In

the 1950s and ‘60s, when the world of art went headlong into the abstract,

artist Max Ginsburg was bringing his view into tighter focus. Ginsburg’s world

wasn’t fuzzy around the edges. His was vivid, animated and all too real.

“Realism is truth and truth is beauty,”

Ginsburg has said, explaining his love of a

style that was not being taught when he was a student, and shunned when he was

a teacher. Even today, the anti-realism sentiment remains strong in a modern

art world that he says too often celebrates difference for difference’s sake.

Ginsburg

was born in 1931 in Paris, but from the age of 2 he was raised in Brooklyn,

N.Y., the son of a painter and a pharmacist. From living room labor meetings to

growing up Jewish during World War II, Ginsburg was exposed early to social

turmoil, political activism and the hardships of poverty and oppression: To

view it all, one had to look no further than the streets of New York, where

Ginsburg’s eyes linger to this day, most recently at the Occupy Wall Street

demonstrations.

He

grew up with racial prejudice, anti-Semitism and the fear of being murdered by

the Nazis. But he was also exposed to left-wing and progressive thinking in

reaction to the world around him. His father, the painter, encouraged his

interest in art. His mother, the pharmacist helped organize a union in the

hospital where she worked and nurtured Max’s political will.

Coffee Break

“That

was the beginning of my feelings about the world, about the social structure,

the ideas that took place,” Ginsburg says of his environment as a youth. “And

that’s the beginning of why I began to paint more like I did.”

Ginsburg

studied at the legendary High School of Music and Art and then at Syracuse

University, holding fast as a student of realism even as the world went head

over heels for abstract expressionism and assorted related ’isms. He became a

teacher at the High School of Art and Design in 1960, and he did commercial

illustrations from 1980 to 2004.

If

realism wouldn’t sell in the gallery, it would on the cover of romance novels,

but only to sell unrealistic concepts. “During my years in illustration, I was

trying to make a living. Painting these illustrations required a high degree of

skill, but unlike my fine art my personal expression of reality was missing.”

The writing may be one step short of dismal but the cover paintings by Masters like Ginsburg are another story altogether. And they pay the bills for many a struggling artist allowing them, like Max, to perfect their work and explore less lucrative avenues of expression.

Ginsburg

is a realist’s realist, from style to subject. His paintings project a simple

honesty that is as complex as any moment in time. He paints the social

condition, both beautiful and brutal, incorporating his own political views.

His

“War Pieta” scene is rendered through precise strokes as a bloodied American

soldier dying in his mother’s arms on an Iraqi battlefield. The scene expresses

Ginsburg’s condemnation of “blood for oil,” using the Renaissance Pieta imagery

to make a point.

In

September, Ginsburg came out with a new book, “Max Ginsburg ~ Retrospective” of

his decades of work as a fine artist, teacher and illustrator. It includes more

than 150 of his paintings, some of which are now part of a large retrospective

exhibit (1956 to 2011) at the Butler Institute of American Art in Youngstown,

Ohio.

In

a recent conversation with Ginsburg, the 80-year-old artist talked passionately,

and sometimes quite emotionally, about his years as an artist, a teacher and a

friend of the people in his paintings.

Among

his greatest memories is volunteering his time, early in the mornings, to teach

students the technique of realistic painting, providing an opportunity not

available in the regular high school curriculum. It was a role he relishes to

this date, but true to the time, one that many school administrators and

teachers in the union could not understand or disagreed with.

“Peace March,” above, 48” x

70” oil on canvas, 2007, shows an array of people, young and old, joining in a

procession in New York City. The key for Ginsburg was their expression of

determination.

Joanne Zuhl:

And your own fellow painters couldn’t understand that either?

Max

Ginsburg:

They didn’t like the fact that we were teaching “traditional old-fashioned” realism. But from my point of view, because realism is not in vogue, it is no justification for rejecting it. I feel realism in art, like truth, is aesthetically beautiful. I also feel that it communicates ideas strongly. If you look at my more recent work, like “War Pieta,” “Torture Abu Ghraib,” or “Homeless,” you see the emotion strongly expressed.

And I feel that communication, which is not just cerebral, but also on an emotional level, is an extremely important part of art. So in addition to my aesthetically liking realism, I feel that it has an emotional appeal to all audiences. Artistic realistic skill is important to resonate the message with the public. It’s not just the subject alone; it’s that it’s realistically done. There are abstract artists who agree with me on many social issues, but the communication of their ideas do not have as strong an impact with people as a realistically painted work.

Audiences are not exposed to this kind of art because the art establishment discourages its development and exhibition opportunities, and this lack of artistic freedom is an injustice.

J.Z.:

The people in your paintings look like people I know, they’re not symbols, or composites, an idea, or metaphors. They look like my neighbor, like people I see walking down the street.

M.G.:

They are.“Coffee Break,” 16” by 16” oil on canvas, 2007, shows a Gulf War veteran, draped in the American flag, under the watchful stare of a policeman.

J.Z.:

It’s almost unnerving, it’s unsettling to look at people in your painting, particularly “Homeless” or the “Foreclosure” or “War Pieta,” it’s like I know that guy.

M.G.:

I’m glad my paintings have communicated. Identification with the people about the social condition is my intention. I want the people in my paintings to be real people, individuals, not stereotypes without individuality. I try to apply John Keats’ phrase, “Truth is beauty” in my art. Facing the truth is beautiful, avoiding it is ugly. Capturing the reality of individuals is beautiful, falsifying and covering up is not.Yes, my “Foreclosure” painting was unnerving. Some felt it was too melodramatic; some people thought the melodrama was good. It is outrageous that people are being thrown out of their homes. Does greed and profit come before humanity? Melodrama is justified for real-life issues, not only for biblical narratives.You don’t need a metaphor to explain something in emotional terms today. Don’t be afraid to be a nonconformist on behalf of humanity.I felt the same way about my “War Pieta.” I was so outraged about this war that I felt that it was necessary to express my emotion, no holds barred.

“War Pieta,” 50” x 60” oil on

canvas, 2007, expresses Ginsburg’s disgust for the “blood for oil” policies

overseas, using the Renaissance imagery of the Madonna and Christ in the Pieta.

J.Z.:

How is Occupy Wall Street fitting into your artwork? Are you going to paint that?

M.G.:

I went down there a few times. I’m 80 years old, so I don’t know if I want to get arrested at this point. But I did go down there. And once I even painted with two friends. It was a matter of showing how I and other artists identify with this movement. And to identify, you’ve got to be there and show what you do. But I was there as another body among the people, the 99 percent, when they marched to City Hall. And I expect to go down more.The Occupy Wall Street images are exciting. The action and determination of the mostly young people is a great idea for a painting, but right now I have been in the midst of a painting about unemployment. There are many figures and emotions involved, able-bodied people who don’t have jobs, a sense of desperation.Some are sullen. Some have pride. Some are angry. All kinds of people: men, women, laborers, various kinds of workers as well as those who have been calling themselves the middle class for years. This is the kind of painting that will take months to do. But the Occupy Wall Street idea is captivating and has a positive thrust. I may be doing two paintings at one time.

J.Z.:

Will we see the work that you created from that?

M.G:

I hope so.

J.Z.:

You mentioned that you are inspired by Goya and Picasso. …

M.G.:

In terms of style, I’m more inspired by Caravaggio and Rembrandt, because their style is more realistic. Like I said before, you can identify with realistically painted people. You know them. That’s important to me. In terms of Goya and Picasso, it is the subject matter of Goya’s “Disasters of War” and Picasso’s “Guernica” that inspired me and, more importantly, gave me “cover” in the art world of today, where painting political subjects are avoided and even disdained.

J.Z.:

“Torture Abu Ghraib,” that is a difficult painting to look at.

M.G.:

I know. A lot of people tell me that. Torture is a terrible thing, but it is just as bad when artists and cultural workers in general hide the truth, like was done in totalitarian countries, and I’m sorry to say it even happens too often in our country.

J.Z.:

I’m wondering, in this highly documented world, what role your paintings, the realism, can play today. I can look at pictures of Abu Ghraib. I can see the images of the protests and of Occupy Wall Street. All of that’s coming to me in the realism of photographs and film. What role does a painting play in chronicling all of this?

M.G.:

I just think that painting, or art, plays a role. It plays a role of expressing the feelings of a particular time and place, from a personal point of view. This is the point of view of the artist who is living in that particular time and place. And I feel that this communication can be stronger in personal terms than when you take a photograph. But photographs are powerful and very important. Also, painting is just one of many forms of expression and should be free to express even the most inhuman conditions.It’s the subject matter, but also the expression or the realistic painting of the subject matter, that brings it closer to the public, and this is what has been denied, in my opinion. A woman stood in front of my “Torture Abu Ghraib” and she was crying. It really did affect her. She said, ‘You just don’t see this kind of work’. This is the kind of thing that communicates. And I don’t think it’s the subject matter alone.

J.Z.:

Looking over the decades of your work, you can see it has changed, from being views and scenes to really being interpretive.

M.G.:

It’s interesting that you say that. I have paintings that are political. But if you’ve looked at some of the paintings I’ve done in 1968 or ‘69, I put in specific symbols to get specific points across more easily.There’s one called the “Flag Vendor,” a white guy with an army jacket selling flags. I thought of the war veteran, and this is all he can do; peddle something on the streets. The irony is that here he is, selling the flag, something he fought for: freedom. But it’s all become so commercialized. He’s not the hero on the battlefield, and I wanted to get that image across. My painting technique is crude here compared to my recent painting and perhaps is not as controversial. In general my work has also become more naturalistic.

J.Z.:

When people look at your works, do you think they come away thinking differently about the politics you’re projecting?

M.G.:

I think people do. But most people will just be affected by the emotion that I’m getting across, and usually if they talk to me, they say they like what I’m painting. I had an exhibition at the Hospital Workers Union Gallery in 2008 and my “Torture Abu Ghraib” painting was there, even though it wasn’t finished.Some union members who looked at it came over to me and said, “Are those American soldiers?” and I said yes.They said, “You ought to be ashamed of yourself. You are un-American. How can you do that? Those boys are fighting for our freedom,” and so on and so forth. So of course I said torture was un-American and we were in Iraq based on fictitious reasons, slaughtering people for oil and greed. And it became pretty much a yelling match and the guards had to come in to be sure it didn’t get violent.But most people are supportive of the painting and especially of my right to express my feelings. And I might add that these people who disagree with me should express their ideas and not prevent me from exhibiting my work, as is our American constitutional right.

J.Z.:

I imagine your audience is either already in your camp or it’s not.

M.G.:

Most people enjoy seeing my paintings, because of the artistic value. Very few raise objection to my subject matter even if they disagree with some of my ideas. Even many abstract artists seem to get a kick out of my work.

J.Z.:

Your paintings get people talking about those things.

M.G.:

I think so. I was mainly painting a slice of life. In every one of those paintings, I’m dealing with the social condition, and maybe most people just pass it by like you pass by life. So you see people of color taking care of rich kids who are usually white. And that’s a social condition that exists, and people take it for granted.In my painting “Nannies and Kids” (2003) you see a black woman solid like a rock caring for two little kids who look like Bouguereau’s angels. And all the nannies around also seem to be from some minority groups. Sometimes you see the reverse, but rarely. Poor people and slaves have been caring for rich people’s kids for centuries. And you wonder sometimes who are the real parents.In “Two Worlds,” there are three guys sitting idle inside a basketball court, whereas on the other side, you have white guys walking around fast like they have things to do. These social relationships make the painting interesting in addition to the design and artistic qualities.

Bus stop

J.Z.:

Having looked at all the decades of civil strife, and where we are today, as an observer of all this, what’s your outlook?

M.G.:

I tend to be an optimist. Nothing is ever perfect, the world or my art. But we are always striving for a more perfect world and a perfect painting.As for the ills in the world, and as part of the 99 percent we have to fight against greed and corruption. At the moment, the Occupy Wall Street movement seems to be positive and encouraging. I think that greed and corruption are going to be around for a long time, and I think that as a human being and as an artist, I will feel like a better person if I’m part of the 99 percent who are opposing it. And my art is a part of my expression.Sure, it would be nice if there were more fairness around and so on, but I guess it’s always going to be a battle, because there’s always a certain amount of greed and hypocrisy going on.

J.Z.:

I feel like you do, but I am energized by the Occupy Wall Street movement.

M.G.:

Me too! But I was energized when the Allies defeated fascism. I was energized when Martin Luther King Jr. led the struggle to end segregation and when unions enabled workers to enjoy a better standard of living.But then there were setbacks. The 1 percent took their factories overseas to become super wealthy, making thousands of workers unemployed, and the Supreme Court ruled corporations to be people and the so-called “middle class” is realizing they are really part of the poorer 1 percent. So it is energizing to see our Occupy Wall Street movement fighting back.

All images

courtesy of Max Ginsburg.

To

see more of Max Ginsburg’s work, and to order copies of his new book GO HERE

Just WOW!

ReplyDeleteThank you

O. Klastat

Excellent piece, as usual.

ReplyDeleteTwo links for you, one to make you puke: http://www.cjpac.ca/

One to give you hope: www.codoh.com

My pleasure Klastat. This man is a national treasure... he seems to be human first, Jewish well not so much, considering his subject matter.

ReplyDeleteAnonymous. You are right. The first link is frightening and hideous and I was SOOOO tempted to put in a few comments at what I read but knew it would not be worth the effort to deal with the backlash.

The second link, tyvm, I will enjoy sharing material I find there. Some good stuff.

Thank you both for dropping by.